Madam Walker’s Mentors, Sister Friends & Rivals

I’ve written a lot about Madam C. J. Walker’s professional and financial achievements, but to truly understand who she was at her core, I’ve also examined her relationships with other women: her mentors, her sister friends and her rivals.

Madam C. J. Walker circa 1913 (Madam Walker Family Archives/aleliabundles.com)

Madam Walker is perhaps best known as a millionaire entrepreneur and hair care industry pioneer, who defied the odds. Behind that public persona is a more private person who valued and benefited from her friendships with other women.

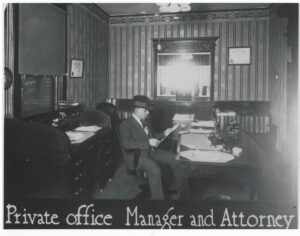

This is not to ignore the men in her life. Her three brief marriages – one husband died and the other two cheated on her – surely motivated her to be self-sufficient. She made much wiser choices in selecting her male business associates, especially Freeman B. Ransom, the attorney who became the Walker Company’s longtime general manager. And she valued business and political collaborations with men like Indianapolis Freeman publisher George Knox, Crisis editor W. E. B. Du Bois, Tuskegee Institute principal Booker T. Washington, musician James Reese Europe and Messenger publisher A. Philip Randolph.

Madam C. J. Walker Mfg. Co. Atty F. B. Ransom circa 1912 (Madam Walker Family Archives)

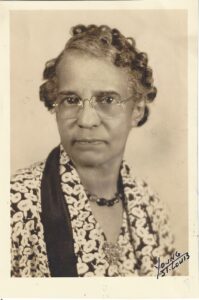

And of course her relationship with her daughter, A’Lelia Walker, is central to understanding what made her tick. (I’ve written about this in On Her Own Ground: The Life and Times of Madam C. J. Walker and will have much more to say in my in-progress book, The Joy Goddess of Harlem: A’Lelia Walker and the Harlem Renaissance.)

A’Lelia Walker, daughter of Madam C. J. Walker (Madam Walker Family Archives)

But it is Madam Walker’s early experiences of being helped by other women that made her so devoted to empowering her sales agents and to supporting causes and organizations that helped girls and women. “I am not merely satisfied in making money for myself, for I am endeavoring to provide employment for hundreds of women of my race,” she said at the 1914 National Negro Business League Convention.

In 1917, at the first national convention of the Madam C. J. Walker Beauty Culturists Union, she implored the delegates to use part of their earnings to better their communities. “I want my agents to feel that their first duty is to humanity,” she said. “Let the world know that the Walker agents are ready to do their bit to help and advance the best interests of the Race.”

When Sarah Breedlove McWilliams moved from Vicksburg, Mississippi to join her older brothers in St. Louis in 1888, she was a 20-year old widow with a two-year old daughter. It was the women of St. Paul African Methodist Episcopal Church and the Mite Missionary Society who helped her see that she could aspire to something more than a life of drudgery as a washerwoman.

Jessie Batts Robinson, St. Louis teacher and clubwoman, who mentored Madam Walker (Madam Walker Family Archives)

Jessie Batts Robinson, a schoolteacher and St. Paul’s member, took a particular interest in Sarah and her daughter. The home Jessie shared with her husband (and St. Louis Argus editor), Christopher “C. K.” Robinson, was a refuge for the struggling young mother. As national officers of the Knights of Pythias and the Court of Calanthe, they exposed Sarah to the powerful network of black fraternal organizations.

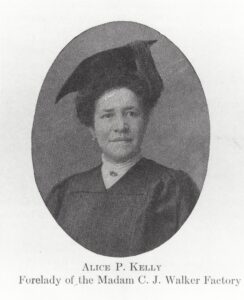

After she founded the Madam C. J. Walker Manufacturing Company in 1906, Madam Walker intentionally surrounded herself with skilled and educated employees. She had a talent for identifying leaders and encouraging them to shine. Aware that her own lack of formal education could be a hindrance, she sought employees who could help shore up her deficits. She considered it a coup that Alice Kelly, dean of girls at Kentucky’s Eckstein Norton Institute, agreed to join the Walker Company as “forelady” – or manager – of her factory.

Kelly also served as her private tutor and sometimes traveling companion. Violet Davis Reynolds, who began working at the Walker Company as a secretary in 1914, later described the role Kelly played in helping Walker polish her presentations: “Whenever I traveled with them, I remember Madam asking Miss Kelly immediately after her speech, ‘How did I do? How can I do better?’”

Alice Kelly, Manager of the Madam Walker Factory (Madam Walker Family Archives)

That desire to improve – from her handwriting to her grammar – was critical to her success.

As with any successful entrepreneur, Madam Walker also had competitors, most notably Annie Turnbo Pope Malone. It is true that Sarah Breedlove McWilliams sold Malone’s Poro products for about a year in St. Louis and then in Denver. Not long after she married Charles Joseph “C. J.” Walker in early 1906, there was a rift of some kind between the two women that caused Madam Walker to sever ties with Malone. By April of 1906 Madam Walker was selling her own line of hair care products.

I’ve written about this fissure in On Her Own Ground and have expanded upon the rivalry in a recent blog article (“The Facts about Madam Walker and Annie Malone”) where I address the difficulty in documenting whether Malone was a millionaire, too. We are fortunate that F. B. Ransom and Violet Reynolds were such conscientious record keepers. As a result, thousands of pages of Madam Walker’s personal and business correspondence are preserved at the Indiana Historical Society. There is no comparable set of records for Annie Malone or the Poro Company.

After decades of research, I’ve come to believe that the relationship with Malone was an important catalyst that helped Sarah Breedlove McWilliams escape St. Louis and a troubled second marriage. But I’ve also come to think the relationship was more transactional than collaborative.

Both women were successful entrepreneurs and philanthropists whose legacies are important in the history of American business. But these two women made very different decisions about how they ran their businesses, the people they chose to put in leadership positions and their marketing strategies.

The women whom Madam Walker would have named as her mentors are Jessie Batts Robinson and Alice Kelly. Among those she truly admired and counted as friends were women like anti-lynching activist Ida B. Wells, Mary Burnett Talbert (the NAACP organizer and former National Association of Colored Women president who led the drive to preserve Frederick Douglass’s home) and educator Mary McLeod Bethune.

Ultimately Madam Walker’s story is one of women empowering and supporting each other, then using their leadership and financial profits to better their communities and the lives of their families.

If you’d like to learn more about Madam Walker, we hope you’ll read On Her Own Ground: The Life and Times of Madam C. J. Walker by A’Lelia Bundles.

Other blog articles

Recent Comments