The Facts about Madam C. J. Walker and Annie Malone

Professor Tyrone McKinley Freeman, who teaches at Indiana University’s Lilly Family School of Philanthropy, has described the impulse to compare the fortunes of Madam C. J. Walker (1867 – 1919) and Annie Malone (1877* – 1957) as “the first millionaire sweepstakes.” In my observation, this “who was first?” battle has become petty, contrived and counterproductive.

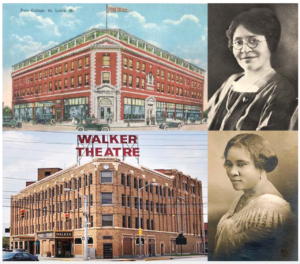

Poro and Walker Building

For a variety of reasons, the now century old rivalry between Madam Walker and Annie Pope-Turnbo Malone continues posthumously with people taking sides in unresolved battles on social media. Most of the time, I try to stay on the sidelines because I long ago learned that it is impossible to change the mind of someone who has no interest in looking at facts and documentation. But for those of you who are open to considering facts, I offer the following information:

There’s no doubt in my mind that Madam C. J. Walker and Annie Malone both are important historical figures who made major contributions as early twentieth century hair care industry pioneers and philanthropists. It is true that Madam Walker sold Malone’s Poro products in St. Louis and in Denver in 1905 and 1906 before marrying Charles Joseph “C.J.” Walker and starting her own Madam C. J. Walker Manufacturing Company. It’s also true that Walker was first introduced to the hair care business in the 1890s by her brothers, who were barbers in St. Louis. As well, it is true that neither Annie Malone or Madam Walker was the first to discover the system of cleansing one’s scalp, then applying a thick ointment that was the consistency of Vaseline — with sulfur as the medicinal agent — to heal the severe scalp infections that were rampant in the early 1900s. It was a time when hygiene was quite different because most Americans lacked in door plumbing. In fact, the remedy they both used had been around for centuries. The basic recipe appears in medical texts as early as the 1700s and was used in other products including Cuticura as well as those manufactured by other black-owned companies during the 1800s. As amazing as both women were, neither was the first to manufacture hair care products for black women. Just a little bit of thought makes it clear that black women had been styling their hair since ancient times.

As a long time journalist and as a biographer who writes non-fiction (i.e. FACT-based) books, I also believe it is important to document one’s assertions and to present accurate information…even on social media where myths and misinformation abound.

Much of the primary source research about the relationship between Walker and Malone first appeared in my book, On Her Own Ground: The Life and Times of Madam C. J. Walker (Scribner, 2001). I was careful to include citations for the newspaper articles and correspondence that documented my assertions in very detailed endnotes. More recently, I wrote a blog post “Madam Walker’s Mentors, Sister Friends and Rivals” that adds to the information about Walker and Malone, as well as the women to whom Walker was close, like St. Louis school teacher Jessie Batts Robinson and anti-lynching activist Ida B. Wells.

Madam C. J. Walker (Credit: Madam Walker Family Archives)

SALES FIGURES FOR MADAM WALKER AND ANNIE MALONE: Since the publication of On Her Own Ground, other authors have written books and articles about Annie Malone. A few years ago, I began to notice “$14 million” as a claim for Malone’s net worth, first in Neema Barnette’s mini-doc video about Malone and then in articles and on social media posts. In 2018, Shomari Wills made the same claim in his book, Black Fortunes: The Story of the First Six African Americans Who Escaped Slavery and Became Millionaires, a poorly researched and error-filled book that had to be revised by his publisher because of the easily found mistakes. For reasons that elude me, he distorted the details of Madam Walker’s life and entirely upended the facts of her appearance and impact at the 1912 National Negro Business League convention.

Because that “$14 million” figure that Wills and others used was new to me, I did additional research to try to learn the origin of the claim. In addition to research I had been gathering for more than 40 years about Walker and Malone, I did an extensive survey of historical newspaper databases on Newspapers.com, Proquest and Genealogybank.com, which now include dozens of black newspapers from the late 1800s and early 1900s.

The first time I was able to find a reference to the $14 million figure was in a 1957 Chicago Defender obituary (“Annie T. Malone Rites at Bethel,” Chicago Defender, May 15, 1957), which read: “Once regarded as the world’s richest Negro woman, her wealth at the peak of her career in the 1920s was estimated at $14 million.”

Two weeks later, the Defender repeated the $14 million figure in another article “How Annie Malone Made, Lost a Fortune.”

In December 1962, the Defender again repeated the $14 million figure.

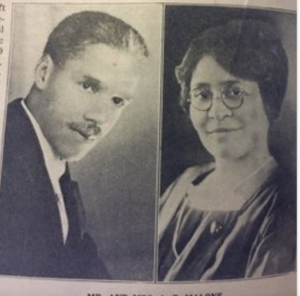

Annie Malone

But no documentation or business records for this claim were cited in the articles and the figure had never appeared in newspaper reports prior to Malone’s death in 1957. Without such documentation or prior contemporaneous reporting during Malone’s lifetime, the figure seems to be drawn from thin air.

Just as misinformation goes viral today, it seems to have gone viral in 1957 and then to have been resurrected in 2020.

When On Her Own Ground first was published in 2001, I estimated Madam Walker’s personal wealth (homes, real estate investments, jewelry, cars, clothing, furniture, etc) to be between $600,000 and $700,000. However, a business historian pointed out to me a year later that I had failed to include the value of Madam Walker’s company in my estimation of her wealth. When one takes into account the sales for the last two years of her life and the year following her death, I was advised that the value of her company, had it been sold on the day of her death, would have been between $1 million and $2 million in 1919 dollars.

Here are the gross receipts for 1918 – 1920 (as documented in Walker Company annual reports and tax records in our Madam Walker Family Archives and in the Walker Collection at the Indiana Historical Society):

1918 earnings: $275,937.88 (an increase of $100,000 from 1917)

1919 earnings $486,762

1920 earnings: $595,353 (or $9,272,135.87 in 2020 according to Dollar Times Calculator)

We are fortunate that we can document Madam Walker’s sales because of the voluminous records that were preserved from the Madam C. J. Walker Manufacturing Company. Unfortunately, similar documentation does not exist for the Poro Company. Unless such records surface, there is no way to prove the claims about Malone’s wealth.

During the last four decades, I’ve created a file of hundreds of articles that mention Malone or Poro between 1903 and the time of her death in 1957. Some of those articles quote officials of the Poro Company regarding the claims for annual sales and company value. I have not found any articles prior to Madam Walker’s death in 1919 or Annie Malone’s death in 1957 that claimed that Malone was “worth $14 million.”

Instead I have found the following:

In November 1913 the Cleveland Gazette, where Annie (then Pope-Turnbo) frequently advertised, the Doings of the Race columnist wrote, “An expert going over the books found the receipts from the sale of hair preparations and agents fees total from $100 to $150 per day.” The Chicago Defender also carried a story giving the $100 to $150 per day” figure.

That $100 to $150 per day would be between $36,500 and $54,750 annually if received seven days a week or between $26,100 and $39,150 annually based on Monday through Friday receipts.

In August 1915, in response to a law suit brought by Walter Majors (a former Malone business partner who sued her for reneging on a share of the 1913 profits she had promised him), a report of the earnings of the previous 33 months was $63,650.03 gross with $24,333.60 net. Another article says the period was “fourteen months” with a “monthly net profit of $1,738.” (14 x $1,738 = $24,333.60).

1918: “A $50,000 Corporation with $250,000 Yearly Business…From last year’s statistics, presented [to] the Bee reporter, is shown in round numbers $250,000 business done.” (“Notable Career of Prof. and Mrs. A.E. Malone,” Washington Bee, August 31, 1918) [Walker’s gross receipts that year, as documented in the annual report prepared by her attorney, were $275,937.88.]

1924: In November, the Topeka Plaindealer reported that Malone had “paid $38,408 income tax for 1923. Her business represents an investment of $750,000.” (“She Is Solving the Race Question,” Plaindealer (Topeka, KS), November 14, 1924)

1926 “Mrs. Malone is probably the Race’s leading business woman and is known to be worth several millions of dollars.” [though I will point out that this reporter cites no documentation] (“Former Banker’s Home Brings Nearly $50,000,” Philadelphia Tribune, Jan 30, 1926)

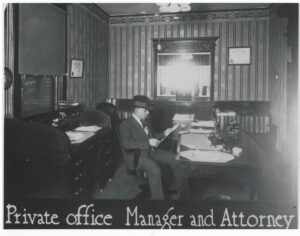

Aaron Malone and Annie Pope Turnbo married in 1914

WHY IS MADAM WALKER MORE WELL-KNOWN THAN ANNIE MALONE: There are many possible reasons why Madam Walker is more well-known today than Annie Malone. Madam Walker died at the height of her fame in May 1919 with her wealth intact while Malone experienced business and reputational setbacks during the 1920s after a contentious divorce from Aaron Malone, who worked to turn some of her employees against her and to undermine her leadership role.

Madam Walker had a knack for hiring and empowering strong leaders who enhanced her company. Her carefully selected executive team included Freeman B. Ransom, the attorney who guarded against legal threats, while Malone was involved in a decades long lawsuit brought by Walter Majors, a former business partner, who accused her of failing to pay a portion of profits promised to him in 1913. (Among the articles that document this legal battle is “Referee Finds Against Beauty Specialist,” Indianapolis Freeman, August 28, 1915.)

Madam C. J. Walker Mfg. Co. Atty F. B. Ransom circa 1912 (Madam Walker Family Archives)

While Attorney Ransom steadfastly paid Madam Walker’s personal and corporate federal income taxes, Malone disputed her federal tax assessment and faced a large unpaid federal tax bill during the 1940s.

Madam Walker’s secretary Violet Davis Reynolds, who worked for the Walker Company from 1914 until 1979, kept meticulous records and preserved thousands of Walker’s personal letters and financial documents, which are housed at the Indiana Historical Society. There is no comparable body of records for Annie Malone or the Poro Company.

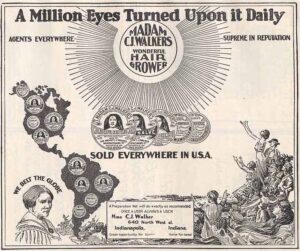

Madam Walker advertised heavily in the black press and cultivated relationships with black editors and publishers. Like her contemporaries Helena Rubinstein and Elizabeth Arden, she created national distribution platforms for her products. She traveled to the Caribbean and Central America in 1913 to expand her market internationally.

Madam Walker advertised in dozens of black newspapers.

Another factor may be her daughter A’Lelia Walker’s suggestion that they establish a presence in Harlem in 1913 just as this uptown Manhattan neighborhood was becoming a political and cultural mecca for African Americans. A’Lelia Walker operated the Walker Beauty School and Salon in Harlem, then converted a floor of their 136th Street townhouse into The Dark Tower, which became an iconic gathering place for the artists, writers, musicians, actors and celebrities of the Harlem Renaissance.

By the mid-1970s most of the Poro and Walker Beauty Schools had closed. I have not been able to determine when the Poro Company stopped manufacturing its line of hair care products. The Madam C. J. Walker Manufacturing Company never went out of business. The trademark was sold by the Madam Walker trustees in the early 1980s to an entity that manufactured some of the original formulas for the next three decades.

In 2013 Richelieu Dennis, founder of Sundial Brands, acquired the Walker trademark for cosmetics and hair care products and revived the line with all new formulas. Today the MCJW line is sold exclusively at Walmart stores and at Walmart.com.

Madam Walker’s legacy also benefits from two very tangible reminders. The Madam Walker Legacy Center in Indianapolis is a National Historic Landmark. Villa Lewaro, the mansion designed by architect Vertner Tandy (a founder of Alpha Phi Alpha), is both a National Historic Landmark and one of the National Trust for Historic Preservation’s designated National Treasures.

Villa Lewaro, estate of Madam C. J. Walker, 1924 (Madam Walker Family Archives0

So who was first? Madam Walker or Annie Malone? If you’ve made it this far in the article, you know that Madam Walker’s wealth can be documented while Annie Malone’s can not. My personal perspective is that Madam Walker’s legacy is measured more in the jobs she created, the philanthropy she dispensed, the lives she changed and the seeds she planted for political activism than in whether she was “the first self-made American woman millionaire,” as the Guinness Book of World Records states.

So those who want to keep arguing this point can have at it.

If you’re interested in learning more about Madam Walker and what’s truly important about her legacy, we urge you to read the new edition of On Her Own Ground: The Life and Times of Madam C. J. Walker or listen to the audio book that I recently recorded. If you happen to be in Indianapolis, we hope you’ll visit the Madam Walker Legacy Center and the Indiana Historical Society where a major exhibit — “You Are There: Madam Walker 1915 Empowering Women” — is up until January 2021.

*Malone was born in 1877. This is a correction.

Recent Comments