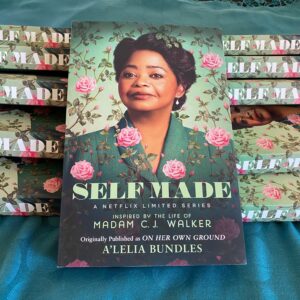

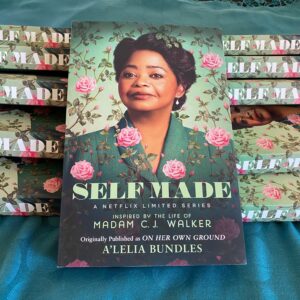

Octavia Spencer as Madam C. J. Walker in “Self Made,” the Netflix series.

When “Self Made: Inspired by the Life of Madam C. J. Walker” — the Netflix series starring Oscar winner Octavia Spencer — premieres on March 20, millions of people around the world will hear Madam Walker’s name for the first time. Thousands of people, who already know at least a little bit about her, will tune in with hopes of learning something new.

I can tell from the reaction on social media that there’s an audience hungry for a story of black women’s empowerment and African American success. There’s also a core group of Madam Walker fans who wrote elementary school reports about her and cosmetologists who followed in her footsteps. They have been waiting for decades for this particular tale. The excitement reminds me of the 1950s and 1960s when those of us of a certain age ran to our televisions on the rare occasions when a black person appeared on The Ed Sullivan Show or when Nat King Cole finally hosted a show in 1956. Of course, in 2020, we have many other viewing options, but as Walker’s biographer and great-great-granddaughter, I’ve come to know how attached many people feel and how personally they identify with anything related to Madam Walker. It’s wonderful to see so much interest and anticipation. In the last few weeks, I’ve received more than the usual number of speaking engagement requests and noticed the announcements of premiere night viewing parties.

But long before Hollywood came calling, many people recognized the power of Madam Walker’s story and identified with her struggles. The seeds that were planted decades ago are in full bloom. A century after her death, Madam Walker is having a moment.

In 1955, I felt my first moment of Walker magic when I opened my grandmother’s dresser drawer and found miniature mummy charms and receipts from the 1922 trip my great-grandmother, A’Lelia Walker took to Cairo.

I was only three years old and had no idea that that discovery would lead me to write, The Joy Goddess of Harlem: A’Lelia Walker and the Harlem Renaissance, a biography that will be published by Scribner in 2021.

When I was a toddler eating dinner with my parents, there was no way for me to know that our silverware — with its “CJW” monogram — would inspire four books, including On Her Own Ground: The Life and Times of Madam C. J. Walker, the biography that provided the factual material for the fictionalized four-part Netflix series.

When I was a toddler eating dinner with my parents, there was no way for me to know that our silverware — with its “CJW” monogram — would inspire four books, including On Her Own Ground: The Life and Times of Madam C. J. Walker, the biography that provided the factual material for the fictionalized four-part Netflix series.

For the 2020 edition — available for pre-order now! with a publication date of March 24 — I’ve written a new epilogue and made a few revisions. I also recorded an audio book which already is available. The book temporarily has been renamed Self Made to tie in with the series promotion.

There are many events and initiatives during the last 50 years that have set the stage for this moment.

I wrote my first report about A’Lelia Walker in 1970 when I was a senior in high school. As a student at Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism in 1975, I was encouraged by Professor Phyl Garland to write my master’s paper about Madam Walker. At the time, there still was no major biography of Madam Walker or A’Lelia Walker.

Stanley Nelson’s 1987 “Two Dollars and a Dream,” was the first documentary about Madam Walker. Nelson, whose grandfather Freeman B. Ransom was general manager and general counsel for the Madam C. J. Walker Manufacturing Company, also directed and produced “BOSS: The Black Experience in Business” a 2019 nonfiction film that includes historically accurate information about Madam Walker.

Here’s the transcript and the video.

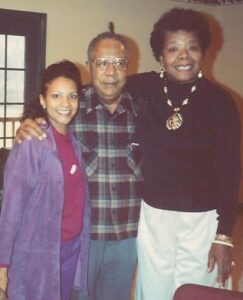

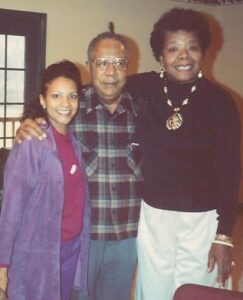

In 1982, Alex Haley, whose fame from the 1976 Roots miniseries still was cresting, approached us about producing a Madam Walker project. For the next several years, Alex was a helpful mentor as I traveled to more than a dozen American cities doing primary source research and interviewing nearly 20 people who had known, worked with or been friends of Madam Walker and A’Lelia Walker.

In 1982, Alex Haley, whose fame from the 1976 Roots miniseries still was cresting, approached us about producing a Madam Walker project. For the next several years, Alex was a helpful mentor as I traveled to more than a dozen American cities doing primary source research and interviewing nearly 20 people who had known, worked with or been friends of Madam Walker and A’Lelia Walker.

On a freighter trip from Long Beach, California to Guyaquil, Ecuador with Alex and two other writers, I finished the manuscript for Madam C. J. Walker: Entrepreneur, a young adult biography published in 1991.

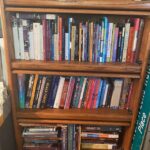

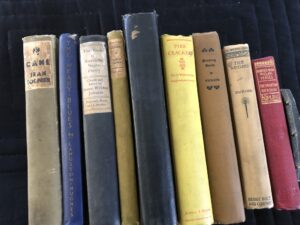

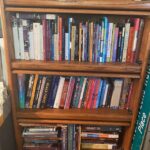

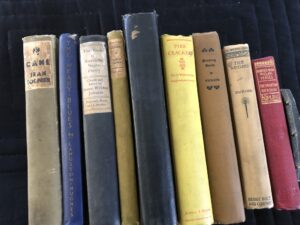

It’s stunning to think this was the first book length biography of Madam Walker ever published, especially now that my personal library is filled with more than 200 books that chronicle Madam Walker’s life from Tiffany Gill’s Beauty Shop Politics, Noliwe Rooks’s Hair Raising and Kathy Peiss’s Hope in a Jar to Hillary and Chelsea Clinton’s The Book of Gutsy Women, Jean Case’s Be Fearless and The Undefeated’s The Fierce 44.

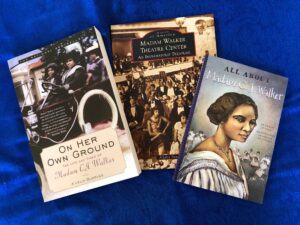

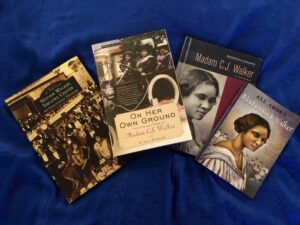

Madam Walker Books in my personal library

And the scholarship continues. Indiana University professor Tyrone McKinley Freeman’s Madam C. J. Walker’s Gospel of Giving: Black Women’s Philanthropy during Jim Crow will be published in November. Since the 1970s, many people have worked together on a range of initiatives to preserve Madam Walker’s legacy. Among the projects:

a campaign for the 1998 Madam Walker U. S. postage stamp

restoration of the Madam Walker Legacy Center in Indianapolis

designation of Villa Lewaro as a National Trust for Historic Preservation National Treasure

digitization of more than 40,000 items in the Madam Walker Collection at the Indiana Historical Society where a 16 month Madam Walker exhibition — You Are There: Madam Walker 1915 –– opened in September 2019

A’Lelia Bundles and Richelieu Dennis, founding CEO of Sundial Brands

renaming of 136th Street at the corner of Malcolm X Boulevard (Lenox Avenue) as Madam C. J. Walker and A’Lelia Walker Place in July 2019

creation of the Madam Walker Family Archives, the largest privately owned collection of Walker records, photographs and memorabilia

dozens of Madam Walker dolls and amazing fine art like Sonya Clark’s large installation at the Austin’s Blanton Museum and Indianapolis’s Alexander Hotel

MCJW, the Madam Walker line of hair care products created by Sundial Brands.

introduction of MCJW, a new line of Madam Walker hair care products manufactured by Sundial Brands and sold exclusively at Sephora.

So, yes, the Netflix series will introduce Madam Walker to many people who otherwise would never have known about her. After you’ve watched the Hollywood version — where the writers have used a great deal of creative license to heighten the drama with characters who didn’t exist and scenes that didn’t occur in real life — we hope you will become curious enough to seek the facts. And of course we hope you will make your way to the new edition of On Her Own Ground as well as some of the blogs about Madam Walker and A’Lelia Walker on this website. There’s also a new audio book that I recorded a few weeks ago.

For updates on all our Madam Walker projects, please visit our Madam Walker Website and follow us on Twitter and Instagram. Click here to sign up for our newsletter.

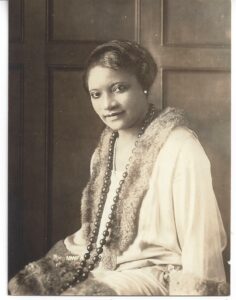

A’Lelia Walker was born 134 years ago today on June 6, 1885.

I’ve written a lot about her since I began researching her life during my senior year in high school fifty years ago. I won’t rehash the basic biographical information, which you can find in my book, On Her Own Ground: The Life and Times of Madam C. J. Walker, and in blog articles like “A’Lelia Walker’s 1924 Visit to Atlantic City” and “A’Lelia Walker Meets Ethiopian Empress Zauditu” on my website.

I’ve written a lot about her since I began researching her life during my senior year in high school fifty years ago. I won’t rehash the basic biographical information, which you can find in my book, On Her Own Ground: The Life and Times of Madam C. J. Walker, and in blog articles like “A’Lelia Walker’s 1924 Visit to Atlantic City” and “A’Lelia Walker Meets Ethiopian Empress Zauditu” on my website.

What I’d like to do today in celebration of her birthday is talk about the person I’ve discovered through extensive research – including her personal correspondence and other primary source documents – rather than the caricature that a number of authors have created.

First and foremost, she will always be known as the daughter of Madam C. J. Walker, the early 20th century hair care entrepreneur and philanthropist. But she also was her own person with interests, personality traits, likes, dislikes and a fascinating circle of friends.

More than I knew when I wrote On Her Own Ground twenty years ago, she was very much a patron of the arts with her own strong passion for music and art that began when she was growing up in St. Louis during the ragtime era of the 1890s. She traveled internationally and understood current events and the politics of Jim Crow. She had an impresario’s instinct for staging extravagant events.

She was a fashion trendsetter with a sharp eye for design. Her parties helped define the Harlem Renaissance. Her Dark Tower cultural salon was legendary. While she was less directly engaged than her mother in causes like the anti-lynching and women’s club movements, she raised money for community and social service organizations.

How Other Authors Viewed A’Lelia Walker

My literary introduction to A’Lelia Walker was through Langston Hughes’s The Big Sea, in which he famously proclaimed her death in August 1931 to be the end of an era. “That was really the end of the gay times of the New Negro era in Harlem,” he wrote. It is Hughes who anointed her “the joy goddess of Harlem’s 1920s” because of her parties and her room-filling personality.

What I have discovered after decades of research, however, is that several other authors who did not know her have repeated second hand, inaccurate and entirely fabricated stories about her. It’s hard to resist wondering if some of them have a need to project a story line onto her life. In their speculation and their failure to do original research, they have relied upon stereotypes and clichés about what they imagine A’Lelia Walker might have done.

What I have discovered after decades of research, however, is that several other authors who did not know her have repeated second hand, inaccurate and entirely fabricated stories about her. It’s hard to resist wondering if some of them have a need to project a story line onto her life. In their speculation and their failure to do original research, they have relied upon stereotypes and clichés about what they imagine A’Lelia Walker might have done.

I very much admire David Levering Lewis’s Pulitzer Prize-winning scholarship on W.E.B. DuBois, but his description of A’Lelia Walker in his widely read When Harlem Was in Vogue set the stage for a great deal of misinformation about her. Just as I discovered while doing research for my four Madam Walker books, I have encountered the same fictionalization of A’Lelia Walker while researching The Joy Goddess of Harlem: A’Lelia Walker and the Harlem Renaissance (forthcoming from Scribner). In all her complexity and contradictions, A’Lelia Walker is an original who needs no embellishment.

I won’t address all the myths today, but here are three of the most glaring.

The Myth of A’Lelia Walker’s Short Attention Span

In 1982 Lewis wrote: “Her intellectual powers were slight. After seven minutes, conversation went precipitously downhill, but those first seven minutes were usually quite creditable.” Among the many authors who have mentioned A’Lelia Walker since then, Steven Watson perpetuated this myth in his 1995 book, The Harlem Renaissance, when he wrote: “One acquaintance cattily declared seven minutes to be her limit for elevated conversation.”

I’ve always found this claim odd. During the early 1980s, I had the good fortune of interviewing a dozen or so of A’Lelia Walker’s octogenarian and nonagenarian friends who regaled me with stories of their social gatherings and travels. To a person, they described A’Lelia’s attention to detail for the elegant parties she orchestrated. I know from her letters how focused she could be when she cared about something. I can’t help but wonder if, by chance, someone actually said she had a seven-minute attention span, that that person may have been someone she didn’t like or with whom she didn’t wish to have a conversation. She could be like that when she wanted to.

The Myth that A’Lelia Walker Didn’t Read Books

Watson seems to have started this rumor when he wrote: “Although she supported Harlem culture, she had little interest in intellectual talk and rarely read books.” More recently Saidiya Hartman paraphrased Watson and others in her 2019 book when she wrote: “[S]he financed the Dark Tower, a literary salon in her palatial home of thirty rooms, although it was rumored that she never read books, only supported their authors.” (The Dark Tower, by the way, was in A’Lelia Walker’s 136th Street townhouse rather than in Villa Lewaro, her Irvington, New York mansion.) Neither Watson or Hartman cites a source for this claim.

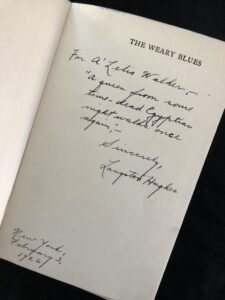

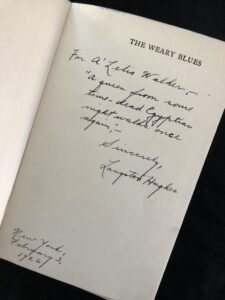

In fact, I have many books from A’Lelia Walker’s personal library, including an autographed copy of Langston Hughes’s The Weary Blues. I also have personal correspondence in which she thanks friends for books they have sent her and talks about how much she loves to read.

In fact, I have many books from A’Lelia Walker’s personal library, including an autographed copy of Langston Hughes’s The Weary Blues. I also have personal correspondence in which she thanks friends for books they have sent her and talks about how much she loves to read.

The Myth that Grace Nail Johnson Wouldn’t Socialize with A’Lelia Walker

One of the most memorable passages in Lewis’s When Harlem Was in Vogue is this: “Not everybody pined for an invitation to her brownstones and her country place. Grace Nail Johnson, the wife of James Weldon Johnson and ‘social dictator’ of Harlem, would as soon have done the Black Bottom on Lenox Avenue as cross A’Lelia’s threshold.”

These sentences have taken on a life of their own in Harlem Renaissance lore and been accepted as factual by readers and authors who have interpreted it to mean that A’Lelia Walker was shunned by Grace Nail Johnson and Harlem’s black elite.

In August 1999 Sondra Kathryn Wilson, the executor of the Johnson estate, told me in an email message that Mrs. Johnson was quite upset about this portrayal.

“It’s a lie,” she told Dr. Grace Sims Okala, her adopted daughter, in an interview recorded some years earlier by Wilson. “Grace and Jim considered the older Mrs. Walker as their friend. Grace often said that the elder Mrs. Walker and her father had similar backgrounds…Grace and Jim didn’t attend a lot of parties. Jim traveled a lot. He was gone so much and when he was home, he was writing. Grace and Jim preferred small dinner parties. If Grace didn’t attend the younger Ms. Walker’s parties, it had nothing to do with Ms. Walker. I know she wouldn’t attend a party if Jim was away. She wouldn’t have gone to Mrs. Walker’s or any other party alone.”

And I know from A’Lelia Walker’s correspondence – including an invitation for an event that lists both A’Lelia Walker and Grace Nail Johnson as hosts – that the speculation about their estrangement is inaccurate. Among other things, the spirit and implication of the story are contradicted by what society columnist Gerri Major, singer Alberta Hunter, artist Romare Bearden and many others told me about A’Lelia Walker during the 1980s.

There is so much more to say about my great-great-grandmother and namesake. Stay tuned for The Joy Goddess of Harlem.

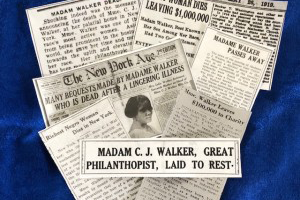

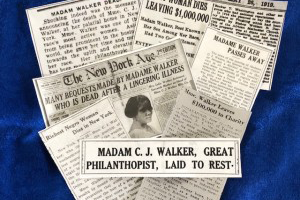

On Sunday morning, May 25, 1919 – exactly 100 years ago this weekend – Madam C. J. Walker died at Villa Lewaro, her Irvington-on-Hudson, New York estate.

A few hours later in black churches across America, ministers talked of her journey from deep poverty in the cotton fields of Delta, Louisiana to president of the international Madam C. J. Walker Manufacturing Company. It was such big news that the announcement also was made at a Negro League baseball game in Chicago that afternoon.

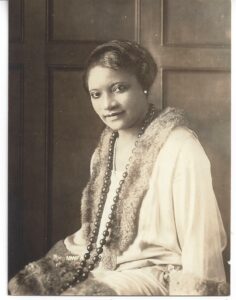

Madam C. J. Walker died on May 25, 1919 at Villa Lewaro, her Irvington, NY estate.

She was born Sarah Breedlove on December 23, 1867 on the same plantation where her parents and older siblings had been enslaved before the end of the Civil War. The first child in her family born into freedom, she would become a millionaire who bequeathed more than $100,000 to her community, including $5,000 to the NAACP’s anti-lynching fund.

By providing job opportunities for the nearly 20,000 sales agents and beauty culturists who sold her Wonderful Hair Grower, she helped them become economically independent. She used her wealth and influence as a philanthropist, patron of the arts and political activist to support black institutions and organizations.

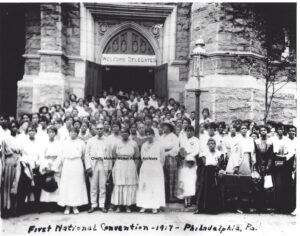

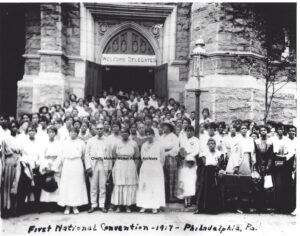

Madam Walker at her first national convention of her sales agents and beauty culturists in 1917.

At her 1917 national convention, she told the delegates that their “first duty” as Walker associates “was to humanity.” During the final session, she and her agents dispatched a telegram to President Woodrow Wilson urging him to support legislation to make lynching a federal crime.

Madam Walker’s funeral on May 30 was a dignified gathering with pallbearers who represented black America’s most prominent civil rights, business and religious leaders. Walker Company employees and agents filed quietly and reverently past her casket in the music room at Villa Lewaro as J. Rosamond Johnson sang “Since You Went Away,” the spiritual he had composed with his brother, James Weldon Johnson.

This year as we observe the centennial of Madam Walker’s death, there is much to remind us of the powerful inspiration her legacy still provides.

Throughout 2019 and 2020 we’ll celebrate with several events including

*the launch of new products in Sundial’s MCJW hair care line at Sephora.com

MCJW, the Madam Walker line of hair care products created by Sundial Brands.

*the re-opening of the renovated Madam Walker Legacy Center in Indianapolis

*the September 19 opening of a Madam Walker exhibition at the Indiana Historical Society in Indianapolis

*the renaming this summer of 136th Street between Lenox and Seventh Avenue in Harlem

*the digitization of 40,000 items from the Madam Walker Collection of letters, photographs, business records and ephemera at the Indiana Historical Society

This spring we’ve already had help celebrating with

*a featured segment about Madam Walker in Stanley Nelson’s PBS documentary, “BOSS: The Black Experience in Business”

*Harlem Eat Up Luminary Award to Madam Walker

*”What Madam Taught Us” in the May issue of Essence

*AAIHS’s five-part Black Perspectives blog forum with articles by scholars who bring new perspectives on Madam Walker’s life

*Our interview with Georgia Public Broadcasting’s Morning Edition host Leah Fleming

ABC News Now’s segment about Villa Lewaro

Ronda Racha Penrice’s NBC BLK feature on Madam Walker

During the last four decades in my role as Madam Walker’s biographer, it has been a joy for me to share her story with a range of audiences from elementary school students and Harvard Business School classes to corporate CEOs and women in the college course at Bedford Hills Correctional Facility.

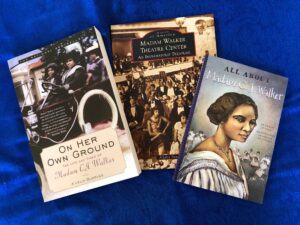

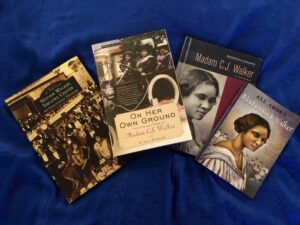

Madam Walker biographies by A’Lelia Bundles

I’m grateful that my book, On Her Own Ground: The Life and Times of Madam C. J. Walker (Scribner/Lisa Drew 2001), is considered the most reliable source for accurate information about Madam Walker and that elementary school students can learn about her in All About Madam C. J. Walker (Cardinal/Blue River Press 2018).

Knowing that Villa Lewaro soon will become a think tank for women of color entrepreneurs under the auspices of the New Voices Foundation brings the story full circle just as Madam Walker dreamed when she moved into the house in 1918.

Follow us on Twitter at @aleliabundles @mcjwbeauty @madamcjwalker

Follow us on Instagram at @aleliabundles @mcjwbeauty

A’Lelia Bundles is Madam C. J. Walker’s great-great-granddaughter and biographer.

July 28 marked the 100th anniversary of the Silent Protest Parade when 10,000 African Americans of all ages marched silently up Fifth Avenue to protest lynchings in America. As they stepped solemnly past thousands of onlookers, the only sounds were the muffled tat-a-tat of a drum and the scrape of shoes across pavement.

Men, women and 800 children had gathered to declare their outrage over the May 15 lynching of 17-year old Jesse Washington in Waco, Texas and the July 2 riot in East St. Louis, Illinois where white mobs murdered more than three dozen African Americans and attacked hundreds.

Silent Protest Parade July 28, 1917 (NYPL Digital Collection)

Today marks another important date related to that demonstration of defiance. On August 1, 1917 members of the NAACP’s New York chapter executive committee traveled from Harlem to Washington, DC to lobby President Woodrow Wilson for support of legislation to make lynching a federal crime.

The group was led by NAACP field secretary James Weldon Johnson and included entrepreneur Madam C. J. Walker, realtor John Nail, New York Age publisher Fred Moore and Rev. Frederick Cullen. They had been assured of a noon meeting with Wilson, but when they arrived at the White House, they were told he was occupied with other matters. Wilson, who had praised D. W. Griffith’s racist movie, “Birth of a Nation,” and instituted segregation in federal offices, had long displayed his disdain for African Americans and their concerns.

Anti-lynching petition delivered to the White House on August 1, 1917 after the Silent Protest Parade in New York. (Credit: Madam Walker Family Archives)

The delegation presented the petition to Wilson’s secretary, Joseph Tumulty, then traveled up Pennsylvania Avenue to Capitol Hill where they met with the few members of Congress who were receptive to their cause. Several months later Congressman Leonidas Dyer — whose St. Louis district was just across the Mississippi River from East St. Louis — introduced a bill that would have required the crime of lynching to be tried in federal court as capital murder. The Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill was passed by the U.S. House of Representatives on January 26, 1922, but was blocked by a Southern Democratic filibuster in the U.S. Senate and never brought to vote.

Beginning in 1882, more than 200 anti-lynching bills were introduced in Congress, but to this day not one has been enacted. In 2005, 80 U.S. Senators approved a resolution apologizing for the U. S. government’s failure to enact this legislation. But it was an apology and not a law.

Even in the 21st Century, there was insufficient will to declare that #BlackLivesMatter.

John Shillady Letter to Madam Walker on May 10, 1919 (Credit: Madam Walker Family Archives)

The NAACP continued its campaign against lynching. During a mass meeting at Carnegie Hall in May 1919, Madam Walker pledged $5,000 to the anti-lynching fund. In his May 10, 1919 letter to Walker, NAACP secretary John R. Shillady noted that it was “the largest [gift] the Association has ever received.”

For more information about the Silent Protest Parade:

Equal Justice Insitute: “A Century after the Silent Protest Parade, Racial Injustice Persists” (July 28, 2017)

Beinecke Library Display July 2017

Black Americans in Congress: “Anti-Lynching Legislation Renewed”

On Her Own Ground: The Life and Times of Madam C. J. Walker by A’Lelia Bundles (pp 203-217)

Happy Birthday, Langston Hughes and Happy Black History Month 2016!

For my A’Lelia Walker biography, I’m in the midst of simultaneously writing three connected chapters right now focused on late 1925 through 1926 about white novelist and music critic Carl Van Vechten’s entrance into Harlem and how the community above 125th Street begins to pivot from being inward and self-affirming — and comfortable with that — to the insertion of and fascination by the white downtown, Prohibition-era gaze.

There’s a lot more that I’d say if I had more time this evening, but I didn’t want to let Langston’s birthday and the beginning of Black History Month pass without taking the opportunity to forecast some of what I’m discovering about A’Lelia Walker’s relationship with Langston.

I am very, very grateful to Langston Hughes for giving me a biographical profile and interpretation of A’Lelia Walker that has guided me for many years as I have learned about her and researched her life.

Langston’s The Big Sea, Arnold Rampersad’s The Life of Langston Hughes Volume I and Emily Bernard’s Remember Me to Harlem

Here’s what Hughes wrote in his memoir, The Big Sea: “It was a period when local and visiting royalty were not at all uncommon in Harlem. And when the parties of A’Lelia Walker, the Negro heiress, were filled with guests whose names would turn any Nordic social climber green with envy.”

His description of one of the parties she hosted in her 80 Edgecombe Avenue apartment captures the spirit of the era: “A’Lelia Walker was the then great Harlem party giver, although Mrs. Bernia Austin fell but little behind…At her “at homes” Negro poets and Negro number bankers mingled with downtown poets and seat-on-the-stock-exchange racketeers…A’Lelia Walker was a gorgeous dark Amazon…A’Lelia Walker was the joy-goddess of Harlem’s 1920s.”

What he wrote has been critical to me because many authors and scholars have written about her in a quite two-dimensional manner. But Langston knew her, so I am inclined to give more credence to his interpretation.

Langston Hughes’s “The Weary Blues” was published in 1926 after Carl Van Vechten introducer Hughes to Alfred Knopf.

My research of the last decade for my in-progress book, The Joy Goddess of Harlem: A’Lelia Walker and the Harlem Renaissance, has allowed me to track when they met.

On January 31, 1926 –when A’Lelia Walker couldn’t attend Langston’s book signing at the Shipwreck Inn at 107 Claremont Avenue near Columbia University — she gave mutual friend and author Wallace Thurman two copies of Langston’s new book, The Weary Blues, with a request for him to autograph them for her.

A few days later, Thurman wrote to Hughes: ““Dear Langston. . .Madam Walker was tickled pink over your inscription. She just must meet you, and will try to arrange to do so as soon as you return.”

In late February, Hughes wrote to Van Vechten about an upcoming trip to New York (from Lincoln University in Pennsylvania where he was still a student): “I think I’ll be in New York Friday. Of course, I want to come see you sometime during the weekend, if you’ll let me…and also this trip I am supposed to meet A’Lelia Walker. Last time, she sent two books for me to autograph for her, but I didn’t’ get to see her.”

Between 1926 and 1931, Hughes attended many of A’Lelia Walker’s parties at her Edgecombe Avenue apartment and at The Dark Tower on 136th Street. On March 1, 1930, he sent this postcard to her from Havana, Cuba, a place they both loved. ” Dear A’Lelia — I think you would adore Havana. (Have you been here?) The people are marvelous, bars and dance halls everywhere and a too-bad beach. All the leading artists and writers and actresses are treating me royally.” A’Lelia Walker, indeed, had been to Cuba in 1918.

When A’Lelia Walker died in August 1931, Langston Hughes wrote this poem, which was read at her funeral.

To learn more about A’Lelia Walker, please check out some of these blog articles about her

A’Lelia Walker and Atlantic City 1924

Discovering The Joy Goddess of Harlem

Today — December 23, 2015 — is the 148th anniversary of Madam C. J. Walker’s birth!

She was born Sarah Breedlove on December 23, 1867 in Delta, Louisiana on the same planation where her parents Owen and Minerva Anderson Breedlove had been enslaved. The first child in her family to be born after the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863, her birth was greeted with much hope and promise. But the Breedlove family’s reality was bleak.

By the time Sarah was seven years old, both parents had died. At ten, she moved across the Mississippi River to Vicksburg, Mississippi with her older sister, Louvenia, and her brother-in-law, Jesse Powell, who was so cruel, she would later say, that she “married at 14 to get a home of my own.” Another blow came with the death of her husband, Moses McWilliams, when she was 20. Now with her two-year old daughter, Lelia (later known as A’Lelia Walker) to raise, she moved up the river to St. Louis, Missouri where her older brothers worked as barbers.

She struggled for the next decade working as a laundress, doing the back-breaking work of washing clothes by hand in tubs and without indoor plumbing. At the end of some weeks, she’d made as little as $1.50, but her dreams for her daughter made her persevere. One day while her hands were buried deep in soap suds, she despaired that life might never get better. But the solution to her problems eventually came when she developed a shampoo and ointment to heal the scalp disease that was causing her to go bald.

Madam Walker died at Villa Lewaro in May 1919.

By the time she died on May 25, 1919 at Villa Lewaro (her mansion in Irvington-on-Hudson, New York), she had founded the Madam C. J. Walker Manufacturing Company and become a millionaire, some say the first self-made American woman to attain that level of financial success.

There is much more to her story of course. How she discovered, developed and marketed her “Wonderful Hair Grower.” How she employed thousands of women as Walker sales agents and beauty culturists. How she spoke up to Booker T. Washington at his 1912 National Negro Business League Convention. How she gathered more than 200 women together for one of America’s first national conventions of women entrepreneurs in 1917. Her prominence as a philanthropist and patron of the arts. Her friendships with Ida B. Wells, W.E.B. DuBois, Mary McLeod Bethune and James Weldon Johnson among others. Her $1,000 contribution to Indianapolis’s YMCA and $5,000 to the NAACP’s anti-lynching campaign. Her activism on behalf of black soldiers, young women and the rights of African Americans.

Her legacy of entrepreneurship and philanthropy still empowers others. She is often mentioned by businesswomen in America and beyond as an inspiration. Her company is discussed and critiqued in a Harvard Business School course. Dozens of students across the nation prepare projects about her every year for National History Day. Countless young girls have dressed up as Madam Walker for Black History Month and Women’s History Month. She is the subject of numerous documentaries, public service announcements and news stories. Several organizations host annual Madam Walker awards luncheons. The Madam Walker Collection of photographs, letters and business records is the most popular collection at the Indiana Historical Society. She was featured on a U. S. postage stamp in 1998. Recently her name was touted as contender for the $20 bill. There are two National Historic Landmarks associated with her life: Villa Lewaro in Irvington-on-Hudson, New York and the Madam Walker Theatre Center in Indianapolis, Indiana.

Here are some of the books in which she has been featured or mentioned in the last couple of years.

Angella M. Nazarian’s Visionary Women (Assouline Publishers)

Cynthia L. Greene’s Entrepreneurship: Ideas in Action (Cengage Learning)

Faith Ringgold’s Harlem Renaissance Party (Amistad)

James J. Madison and Lee Ann Sandweiss’s Hoosiers and the American Story (Indiana Historical Society)

Martin Kilson’s Transformation of the African American Intelligentsia 1880 – 2012 (Harvard University Press)

Diane Radmacher’s Famous Firsts of St. Louis: A Celebration of Facts, Figures, Food & Fun

As we approach the 150th anniversary of her birth, we can say there are more exciting announcements to come in the new year. Stay tuned!

Other blog posts that might interest you

A Family Perspective: Celebrating Madam Walker’s Legacy

Madam Walker’s 1917 Convention: Entrepreneurship and Protest Politics

Madam Walker’s Mansion: The Future of Villa Lewaro

Madam Walker’s August Garden

Woodlawn Cemetery — Burial Place of Madam Walker — Designated National Historic Landmark

Madam Walker Visits the Brothers Dumas in Mississippi

Madam Walker Black History Month 2013

To learn more about Madam Walker, visit our official Madam C. J. Walker website at www.madamcjwalker.com

To order On Her Own Ground: The Life and Times of Madam C. J. Walker and Madam Walker Theatre Center, visit my website at www.aleliabundles.com

Here’s a link to videos about Madam Walker.

Check out Madam Walker on Facebook.

When I was a toddler eating dinner with my parents, there was no way for me to know that our silverware — with its “CJW” monogram — would inspire four books, including On Her Own Ground: The Life and Times of Madam C. J. Walker, the biography that provided the factual material for the fictionalized four-part Netflix series.

When I was a toddler eating dinner with my parents, there was no way for me to know that our silverware — with its “CJW” monogram — would inspire four books, including On Her Own Ground: The Life and Times of Madam C. J. Walker, the biography that provided the factual material for the fictionalized four-part Netflix series.

In 1982, Alex Haley, whose fame from the 1976 Roots miniseries still was cresting, approached us about producing a Madam Walker project. For the next several years, Alex was a helpful mentor as I traveled to more than a dozen American cities doing primary source research and interviewing nearly 20 people who had known, worked with or been friends of Madam Walker and A’Lelia Walker.

In 1982, Alex Haley, whose fame from the 1976 Roots miniseries still was cresting, approached us about producing a Madam Walker project. For the next several years, Alex was a helpful mentor as I traveled to more than a dozen American cities doing primary source research and interviewing nearly 20 people who had known, worked with or been friends of Madam Walker and A’Lelia Walker.

I’ve written a lot about her since I began researching her life during my senior year in high school fifty years ago. I won’t rehash the basic biographical information, which you can find in my book,

I’ve written a lot about her since I began researching her life during my senior year in high school fifty years ago. I won’t rehash the basic biographical information, which you can find in my book,

What I have discovered after decades of research, however, is that several other authors who did not know her have repeated second hand, inaccurate and entirely fabricated stories about her. It’s hard to resist wondering if some of them have a need to project a story line onto her life. In their speculation and their failure to do original research, they have relied upon stereotypes and clichés about what they imagine A’Lelia Walker might have done.

What I have discovered after decades of research, however, is that several other authors who did not know her have repeated second hand, inaccurate and entirely fabricated stories about her. It’s hard to resist wondering if some of them have a need to project a story line onto her life. In their speculation and their failure to do original research, they have relied upon stereotypes and clichés about what they imagine A’Lelia Walker might have done.

In fact, I have many books from A’Lelia Walker’s personal library, including an autographed copy of Langston Hughes’s The Weary Blues. I also have personal correspondence in which she thanks friends for books they have sent her and talks about how much she loves to read.

In fact, I have many books from A’Lelia Walker’s personal library, including an autographed copy of Langston Hughes’s The Weary Blues. I also have personal correspondence in which she thanks friends for books they have sent her and talks about how much she loves to read.

Recent Comments