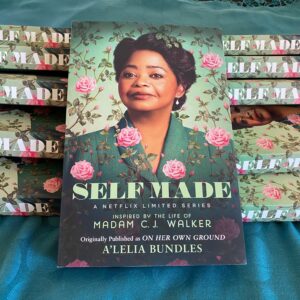

Octavia Spencer as Madam C. J. Walker in “Self Made,” the Netflix series.

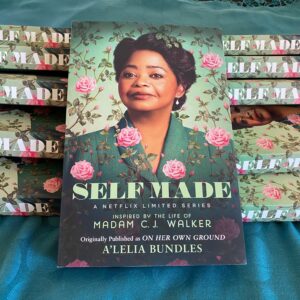

When “Self Made: Inspired by the Life of Madam C. J. Walker” — the Netflix series starring Oscar winner Octavia Spencer — premieres on March 20, millions of people around the world will hear Madam Walker’s name for the first time. Thousands of people, who already know at least a little bit about her, will tune in with hopes of learning something new.

I can tell from the reaction on social media that there’s an audience hungry for a story of black women’s empowerment and African American success. There’s also a core group of Madam Walker fans who wrote elementary school reports about her and cosmetologists who followed in her footsteps. They have been waiting for decades for this particular tale. The excitement reminds me of the 1950s and 1960s when those of us of a certain age ran to our televisions on the rare occasions when a black person appeared on The Ed Sullivan Show or when Nat King Cole finally hosted a show in 1956. Of course, in 2020, we have many other viewing options, but as Walker’s biographer and great-great-granddaughter, I’ve come to know how attached many people feel and how personally they identify with anything related to Madam Walker. It’s wonderful to see so much interest and anticipation. In the last few weeks, I’ve received more than the usual number of speaking engagement requests and noticed the announcements of premiere night viewing parties.

But long before Hollywood came calling, many people recognized the power of Madam Walker’s story and identified with her struggles. The seeds that were planted decades ago are in full bloom. A century after her death, Madam Walker is having a moment.

In 1955, I felt my first moment of Walker magic when I opened my grandmother’s dresser drawer and found miniature mummy charms and receipts from the 1922 trip my great-grandmother, A’Lelia Walker took to Cairo.

I was only three years old and had no idea that that discovery would lead me to write, The Joy Goddess of Harlem: A’Lelia Walker and the Harlem Renaissance, a biography that will be published by Scribner in 2021.

When I was a toddler eating dinner with my parents, there was no way for me to know that our silverware — with its “CJW” monogram — would inspire four books, including On Her Own Ground: The Life and Times of Madam C. J. Walker, the biography that provided the factual material for the fictionalized four-part Netflix series.

When I was a toddler eating dinner with my parents, there was no way for me to know that our silverware — with its “CJW” monogram — would inspire four books, including On Her Own Ground: The Life and Times of Madam C. J. Walker, the biography that provided the factual material for the fictionalized four-part Netflix series.

For the 2020 edition — available for pre-order now! with a publication date of March 24 — I’ve written a new epilogue and made a few revisions. I also recorded an audio book which already is available. The book temporarily has been renamed Self Made to tie in with the series promotion.

There are many events and initiatives during the last 50 years that have set the stage for this moment.

I wrote my first report about A’Lelia Walker in 1970 when I was a senior in high school. As a student at Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism in 1975, I was encouraged by Professor Phyl Garland to write my master’s paper about Madam Walker. At the time, there still was no major biography of Madam Walker or A’Lelia Walker.

Stanley Nelson’s 1987 “Two Dollars and a Dream,” was the first documentary about Madam Walker. Nelson, whose grandfather Freeman B. Ransom was general manager and general counsel for the Madam C. J. Walker Manufacturing Company, also directed and produced “BOSS: The Black Experience in Business” a 2019 nonfiction film that includes historically accurate information about Madam Walker.

Here’s the transcript and the video.

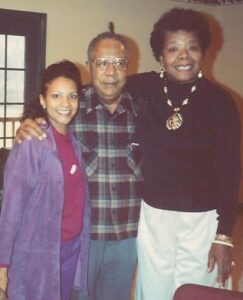

In 1982, Alex Haley, whose fame from the 1976 Roots miniseries still was cresting, approached us about producing a Madam Walker project. For the next several years, Alex was a helpful mentor as I traveled to more than a dozen American cities doing primary source research and interviewing nearly 20 people who had known, worked with or been friends of Madam Walker and A’Lelia Walker.

In 1982, Alex Haley, whose fame from the 1976 Roots miniseries still was cresting, approached us about producing a Madam Walker project. For the next several years, Alex was a helpful mentor as I traveled to more than a dozen American cities doing primary source research and interviewing nearly 20 people who had known, worked with or been friends of Madam Walker and A’Lelia Walker.

On a freighter trip from Long Beach, California to Guyaquil, Ecuador with Alex and two other writers, I finished the manuscript for Madam C. J. Walker: Entrepreneur, a young adult biography published in 1991.

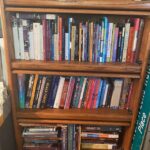

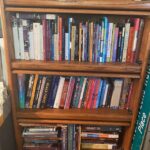

It’s stunning to think this was the first book length biography of Madam Walker ever published, especially now that my personal library is filled with more than 200 books that chronicle Madam Walker’s life from Tiffany Gill’s Beauty Shop Politics, Noliwe Rooks’s Hair Raising and Kathy Peiss’s Hope in a Jar to Hillary and Chelsea Clinton’s The Book of Gutsy Women, Jean Case’s Be Fearless and The Undefeated’s The Fierce 44.

Madam Walker Books in my personal library

And the scholarship continues. Indiana University professor Tyrone McKinley Freeman’s Madam C. J. Walker’s Gospel of Giving: Black Women’s Philanthropy during Jim Crow will be published in November. Since the 1970s, many people have worked together on a range of initiatives to preserve Madam Walker’s legacy. Among the projects:

a campaign for the 1998 Madam Walker U. S. postage stamp

restoration of the Madam Walker Legacy Center in Indianapolis

designation of Villa Lewaro as a National Trust for Historic Preservation National Treasure

digitization of more than 40,000 items in the Madam Walker Collection at the Indiana Historical Society where a 16 month Madam Walker exhibition — You Are There: Madam Walker 1915 –– opened in September 2019

A’Lelia Bundles and Richelieu Dennis, founding CEO of Sundial Brands

renaming of 136th Street at the corner of Malcolm X Boulevard (Lenox Avenue) as Madam C. J. Walker and A’Lelia Walker Place in July 2019

creation of the Madam Walker Family Archives, the largest privately owned collection of Walker records, photographs and memorabilia

dozens of Madam Walker dolls and amazing fine art like Sonya Clark’s large installation at the Austin’s Blanton Museum and Indianapolis’s Alexander Hotel

MCJW, the Madam Walker line of hair care products created by Sundial Brands.

introduction of MCJW, a new line of Madam Walker hair care products manufactured by Sundial Brands and sold exclusively at Sephora.

So, yes, the Netflix series will introduce Madam Walker to many people who otherwise would never have known about her. After you’ve watched the Hollywood version — where the writers have used a great deal of creative license to heighten the drama with characters who didn’t exist and scenes that didn’t occur in real life — we hope you will become curious enough to seek the facts. And of course we hope you will make your way to the new edition of On Her Own Ground as well as some of the blogs about Madam Walker and A’Lelia Walker on this website. There’s also a new audio book that I recorded a few weeks ago.

For updates on all our Madam Walker projects, please visit our Madam Walker Website and follow us on Twitter and Instagram. Click here to sign up for our newsletter.

I’ve written a lot about Madam C. J. Walker’s professional and financial achievements, but to truly understand who she was at her core, I’ve also examined her relationships with other women: her mentors, her sister friends and her rivals.

Madam C. J. Walker circa 1913 (Madam Walker Family Archives/aleliabundles.com)

Madam Walker is perhaps best known as a millionaire entrepreneur and hair care industry pioneer, who defied the odds. Behind that public persona is a more private person who valued and benefited from her friendships with other women.

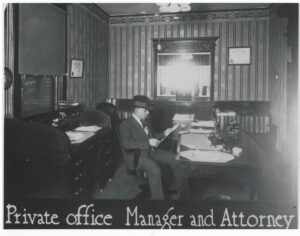

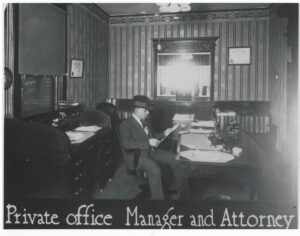

This is not to ignore the men in her life. Her three brief marriages – one husband died and the other two cheated on her – surely motivated her to be self-sufficient. She made much wiser choices in selecting her male business associates, especially Freeman B. Ransom, the attorney who became the Walker Company’s longtime general manager. And she valued business and political collaborations with men like Indianapolis Freeman publisher George Knox, Crisis editor W. E. B. Du Bois, Tuskegee Institute principal Booker T. Washington, musician James Reese Europe and Messenger publisher A. Philip Randolph.

Madam C. J. Walker Mfg. Co. Atty F. B. Ransom circa 1912 (Madam Walker Family Archives)

And of course her relationship with her daughter, A’Lelia Walker, is central to understanding what made her tick. (I’ve written about this in On Her Own Ground: The Life and Times of Madam C. J. Walker and will have much more to say in my in-progress book, The Joy Goddess of Harlem: A’Lelia Walker and the Harlem Renaissance.)

A’Lelia Walker, daughter of Madam C. J. Walker (Madam Walker Family Archives)

But it is Madam Walker’s early experiences of being helped by other women that made her so devoted to empowering her sales agents and to supporting causes and organizations that helped girls and women. “I am not merely satisfied in making money for myself, for I am endeavoring to provide employment for hundreds of women of my race,” she said at the 1914 National Negro Business League Convention.

In 1917, at the first national convention of the Madam C. J. Walker Beauty Culturists Union, she implored the delegates to use part of their earnings to better their communities. “I want my agents to feel that their first duty is to humanity,” she said. “Let the world know that the Walker agents are ready to do their bit to help and advance the best interests of the Race.”

When Sarah Breedlove McWilliams moved from Vicksburg, Mississippi to join her older brothers in St. Louis in 1888, she was a 20-year old widow with a two-year old daughter. It was the women of St. Paul African Methodist Episcopal Church and the Mite Missionary Society who helped her see that she could aspire to something more than a life of drudgery as a washerwoman.

Jessie Batts Robinson, St. Louis teacher and clubwoman, who mentored Madam Walker (Madam Walker Family Archives)

Jessie Batts Robinson, a schoolteacher and St. Paul’s member, took a particular interest in Sarah and her daughter. The home Jessie shared with her husband (and St. Louis Argus editor), Christopher “C. K.” Robinson, was a refuge for the struggling young mother. As national officers of the Knights of Pythias and the Court of Calanthe, they exposed Sarah to the powerful network of black fraternal organizations.

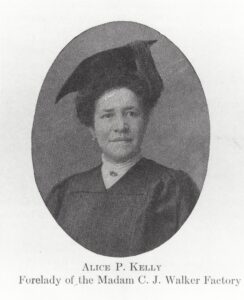

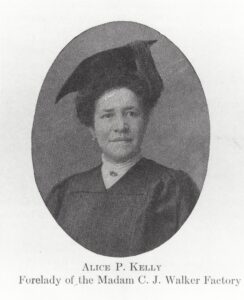

After she founded the Madam C. J. Walker Manufacturing Company in 1906, Madam Walker intentionally surrounded herself with skilled and educated employees. She had a talent for identifying leaders and encouraging them to shine. Aware that her own lack of formal education could be a hindrance, she sought employees who could help shore up her deficits. She considered it a coup that Alice Kelly, dean of girls at Kentucky’s Eckstein Norton Institute, agreed to join the Walker Company as “forelady” – or manager – of her factory.

Kelly also served as her private tutor and sometimes traveling companion. Violet Davis Reynolds, who began working at the Walker Company as a secretary in 1914, later described the role Kelly played in helping Walker polish her presentations: “Whenever I traveled with them, I remember Madam asking Miss Kelly immediately after her speech, ‘How did I do? How can I do better?’”

Alice Kelly, Manager of the Madam Walker Factory (Madam Walker Family Archives)

That desire to improve – from her handwriting to her grammar – was critical to her success.

As with any successful entrepreneur, Madam Walker also had competitors, most notably Annie Turnbo Pope Malone. It is true that Sarah Breedlove McWilliams sold Malone’s Poro products for about a year in St. Louis and then in Denver. Not long after she married Charles Joseph “C. J.” Walker in early 1906, there was a rift of some kind between the two women that caused Madam Walker to sever ties with Malone. By April of 1906 Madam Walker was selling her own line of hair care products.

I’ve written about this fissure in On Her Own Ground and have expanded upon the rivalry in a recent blog article (“The Facts about Madam Walker and Annie Malone”) where I address the difficulty in documenting whether Malone was a millionaire, too. We are fortunate that F. B. Ransom and Violet Reynolds were such conscientious record keepers. As a result, thousands of pages of Madam Walker’s personal and business correspondence are preserved at the Indiana Historical Society. There is no comparable set of records for Annie Malone or the Poro Company.

After decades of research, I’ve come to believe that the relationship with Malone was an important catalyst that helped Sarah Breedlove McWilliams escape St. Louis and a troubled second marriage. But I’ve also come to think the relationship was more transactional than collaborative.

Both women were successful entrepreneurs and philanthropists whose legacies are important in the history of American business. But these two women made very different decisions about how they ran their businesses, the people they chose to put in leadership positions and their marketing strategies.

The women whom Madam Walker would have named as her mentors are Jessie Batts Robinson and Alice Kelly. Among those she truly admired and counted as friends were women like anti-lynching activist Ida B. Wells, Mary Burnett Talbert (the NAACP organizer and former National Association of Colored Women president who led the drive to preserve Frederick Douglass’s home) and educator Mary McLeod Bethune.

Ultimately Madam Walker’s story is one of women empowering and supporting each other, then using their leadership and financial profits to better their communities and the lives of their families.

If you’d like to learn more about Madam Walker, we hope you’ll read On Her Own Ground: The Life and Times of Madam C. J. Walker by A’Lelia Bundles.

Other blog articles

The Centennial of Madam Walker’s Death

We all remember where we were on April 4, 1968. We remember when we first heard that Martin Luther King, Jr. had been shot. We remember learning soon after that he had died. Indeed, that he had been assassinated.

We already had lived through the assassinations of President Kennedy and Malcolm X. We did not know that Robert Kennedy would be killed two months later.

Depending on where we lived, we either watched the riots on television or saw our neighborhoods burn. In my hometown of Indianapolis, the absence of large scale riots was attributed to a speech Robert Kennedy, then campaigning for president, gave in a park that night in a black neighborhood.

We watched the funeral a few days later. We heard Mahalia Jackson sing “Precious Lord.” We wept as we watched the King children and were in awe at Coretta Scott King’s show of strength and dignity.

“The Armor We Still Need” by A’Lelia Bundles in Rochelle Riley’s The Burden: African Americans and the Enduring Impact of Slavery (Wayne State University Press 2018)

“The Armor We Still Need” by A’Lelia Bundles in Rochelle Riley’s The Burden: African Americans and the Enduring Impact of Slavery (Wayne State University Press 2018)

Last year I included my memories of that day and the months that followed in an essay I wrote for Rochelle Riley’s book, The Burden: African Americans and the Enduring Impact of Slavery. Here is an excerpt:

I still can feel the sting. Prickly flares of embarrassment radiate from my ribs. A half-century later, I am isolated and hot. A half-century later, I also am clear that this fiery shame is not justified. But as a teenager, I do not know how to extinguish it. I have no weapons for the battle.

It is the fall of 1968. I am in my high school American history class, in an affluent suburb of Indianapolis. I am the only black student in the classroom, in an overwhelmingly white public school, seated at a desk in the center row, halfway down the aisle.

The day’s topic is the Civil War.

On this day, we are reading from the textbook. My eyes lock on a section titled “Negro Slavery.” It is the first time this semester I have seen a reference to people of African descent. The boldface letters blare from the page.

What I remember from that chapter is this: “Slaves” —not “enslaved people,” as scholars now prefer to say, but “slaves” —were “contented” and well cared for by their kind and benevolent masters.

…I don’t yet know about resistance and revolt. None of my textbooks has included Nat Turner and Harriet Tubman. Ida B. Wells and Frederick Douglass are absent from the curriculum.

…On April 4, 1968, a few months before that history class, I was elected vice president of my school’s student council. Later that day, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in Memphis. Celebration quickly turned to anguish.

The next morning, I learned that a few white parents had called the school to complain about the election. For the most part, teachers and school administrators, who had mentored and nurtured me, also shielded me from that nasty parental bigotry. The next spring, when I ran for student council president, there were uncomfortable undercurrents around race and gender. There had never been a black female in that position. Another candidate who had been involved in student government was my opponent. The principal’s son, who had little previous leadership involvement, ran for vice president. During my campaign speech, I was heckled by a handful of students from a corner of the auditorium. I lost by a few votes.

I don’t remember any particular sense of sadness or defeat, perhaps because I understood exactly what had been engineered. I moved on. I spent part of the summer at a camp for high school journalists at Northwestern University, in a decidedly more progressive environment. I began my senior year as co-editor of the newspaper and had my say through my columns. With a white male classmate, I co-founded a Human Relations Council to navigate racial tensions and build alliances in a 3,400-member student body that was less than 5 percent black.

It was a year of turmoil for America and a year of radicalization for me. I began a journey of self-discovery and self-education. At some point, I read W. E. B. Du Bois’s The Souls of Black Folk. That slim volume was an elixir that offered me a combination of intellectual fireworks, historical facts, and much-needed affirmation.

The Burden includes essays by Rochelle Riley, Herb Boyd, Charlene Carruthers, Patrice Gaines, Paula Madison, Julianne Malveaux, Vann Newkirk, Leonard Pitts, Tim Reid, DeWayne Whickham and Tamara Winfrey-Harris.

You can purchase The Burden here.

William Hendry, who was born in Frederick, VA circa 1760, prepared this will in 1838.

In 1838 when William Hendry of Greene County, Tennessee drew up his will, he included this passage: “It is my will and desire that Nancy McEfee have $300 in place of a Mulatto girl named Delfey [that] I once gave her as a legatee and McEfee gave her back and gave her mother a bill of sale for the girl that she might have [a] chance to free her for which above named $300 McEfee holds some obligation to me to be paid at my death.” [McEfee sometimes appears as McFee.]

I’ve written about Delfey (also spelled Delphia) before. She’s one of my maternal great-great-great-grandmothers and was born about 1808. By all accounts, she is the daughter of William Hendry (b. 1760) and Rose (b. 1790), a woman he owned. Because Delphia was his daughter–and because he seems to have promised Rose that he would eventually free Delphia–he made arrangements in this document and in others to carry out that commitment.

William Hendry values “the Mulatto girl named Delfey,” who is his daughter, at $300.

Seeing the $300 valuation made me curious. What would the equivalent amount be today?

It turns out that a valuation can be interpreted in many ways. MeasuringWorth.com, a website that strives to provide accurate historical data on economic aggregates, distinguishes three categories: 1) the cost or value of a commodity 2) income or wealth and 3) a project (an investment or the construction of something like a canal or cable network).

Here is how Measuringworth.com shows the relative worth today for 1838’s $300

$7,750.00 using the Consumer Price Index

$6,620.00 using the GDP deflator

$68,800.00 using the unskilled wage

$144,000.00 using the Production Worker Compensation

$161,000.00 using the nominal GDP per capita

$3,150,000.00 using the relative share of GDP*

William Hendry’s will was written on June 24, 1838, eight days before he died.

After divvying up his assets to his sons and various other relatives in amounts of $50 for some and $150 for others, Hendry also wrote: “It is my will and desire that the rest of my estate after Sally McCray’s heirs have one hundred and fifty dollars as above named and Nancy McEfee gets her above named $300, which I promised McEfee to leave to her at my death in place of Delfey, the Mulatto girl and for selling Delfey to Rose as she might have a chance to free her…”

Just to put things in perspective: In 1806, two years before Delphia was born, William Hendry sold 45 acres of land in Washington County, Tennessee to a man named David Brown for $150.00. In 1808, a man named Stephen Kirk puchased 202 1/2 acres in Baldwin County, Georgia for $450.00.

So many questions. What a conundrum to own one of your children and to place a value on her as you would a plow or a horse and yet to have bucked custom and provided a legal path for her freedom. What convoluted calculations determined that this child was worth $300 while the bequest to your sons was $50? Who was Nancy McEfee and why was Delphia conveyed to her and then returned?

As I have learned through the years from other Hendry descendants and relatives who have generously shared documents and information, there is much more to Delphia Hendry’s story.

A few months ago, Robert Purvis, reached out to me through Ancestry.com. He and I share William Hendry as a great-great-great-great-grandfather. Robert, who is a descendant of one of Hendry’s sons, directed me to a page on the Race and Slavery Petitions Project website that included a petition filed on October 19, 1833 (five years before William Hendry’s will) for Delphia’s freedom.

Greene County, Tennessee–located in the southeastern corner of the state near North Carolina–in 1888.

Greene County Tennessee Petition 11483304 read: Twenty-five residents of Greene County represent that William Hendrey gave John McFee, his son-in-law, “a Cartin Calored Gal by the name of Delfe” in 1827 and that said McFee “Sold hur to hur mother a black woman for the Sum of thre hundred Dollars”; McFee “gave hur mother a firm bil of Sail for Delfy and She was to Set hur free.” The petitioners point out that said mother cannot emancipate her daughter owing “to an act of the General assembly prohibiting the amancipation of Slaves.” The petitioners therefore pray “your Honourable body to pass a law authorising the County Court of Green to emancipate the sd Delfey.” They further avow that Delfy “is a garl of good Charactor.”

I knew from the emancipation certificate, which my grandfather cherished and had given to me almost forty years ago, that Delphia eventually was freed in 1841, more than two decades before the Emancipation Proclamation of January 1, 1863. But as the 1833 petition shows, there was incredible resistance to her emancipation.

Delphia Hendry carried this document during the 1840s and 1850s to validate her freedom.

The journey to freedom seems to have been formally set in motion in 1827 when Delphia was 19 years old. It was then, as the 1833 petition says, that William Hendry, gave Delphia (“a certain colored gal by the name of Delfe”) to his son-in-law, John McEfee, husband of Nancy Hendry McEfee, one of his white daughters. McEfee, in turn sold Delphia to her mother, Rose, for $300. McEfee, according to the 1833 petition, then gave Rose “a firm bill of sale” that was to allow Rose to set her daughter free. But because Tennessee had a law “prohibiting the emancipation of slaves,” Rose was prevented from freeing her child.

Delphia Hendry’s Emancipation Certificate finally was issued in 1839 after her father’s death.

Five more years were to pass after Rose’s purchase of Delphia with Delphia still not legally freed. In the 1833 document, 25 residents of Greene County Tennessee signed a petition requesting that the county authorize a law to emancipate Delphia. Even though that law was passed, it would take another nine years before Delphia would be emancipated.

More answers simply bring more questions. How in the world did Rose get $300 in 1827? Or was the $300 a credit Rose somehow had accumulated toward some debt Hendry owed her? Did Hendry give his mulatto daughter to his white daughter and son-in-law to settle a debt? Did his daughter, Nancy Hendry McEfee, urge him to free Delphia, who was her half-sister? Or did Nancy “give her back” because there was some kind of sibling rivalry? Who were the 25–presumably white and free–citizens who vouched for Rose and Delphia?

Delphia Hendry’s great-grandson, Marion R. Perry, preserved her Emancipation Certificate and passed it on to his granddaughter. (www.aleliabundles.com)

I do not have any images of Delphia, only this emancipation document that my grandfather, Marion R. Perry–Delphia’s great-grandson–had preserved and laminated many decades ago.

This photo is of her son, Henderson B. Robinson, my maternal great-great-grandfather, who was born in 1824 when Delphia was 16.

Delphia’s son, Henderson B. Robinson, was elected sheriff of Phillips County, Arkansas during Reconstruction. When he and other black elected officials were pushed from office in 1878, he moved his family to Oberlin, Ohio.

He later would move to Ripley, Ohio (a major stop on the Underground Railroad), to Memphis (where my grandfather said he “worked with Robert Church“–Mary Church Terrell’s father–though I have no details of that) and then to Helena, Arkansas where he would become superintendent of prisons and sheriff of Phillips County, and a member of the Arkansas state legislature during Reconstruction. The home he owned there is now listed on the National Register of Historic Places. In 1872 he purchased a 3600 acre farm. After white “Redeemers” pushed African Americans out of elected office in Arkansas and throughout the South in 1878, he moved his family to Ohio and enrolled his children at Oberlin.

In 1880, Henderson Robinson was one of twelve Arkansas delegates to the Republican National Convention. He and 306 of the 756 supported former president Ulysses S. Grant, though James Garfield won the nomination. The Arkansas Democratic Party of that era was composed of men who had ousted black legislators and disenfranchised black voters.

I continue to ponder, to search and to fill in the blanks, not so much about Delphia and Rose and their relationship with William Hendry–which I will never really know–but about how Delphia prepared her son, Henderson, for the world that lay ahead and how Henderson and his wife, Adelaide, taught their children–including my great-grandmother, Ida Robinson Perry–to navigate America during the late 19th century.

H. B. Robinson was a delegate to the 1880 Republican National Convention supporting Ulysses S. Grant.

A’Lelia Bundles is the author of On Her Own Ground: The Life and Times of Madam C. J. Walker, a biography of one of her great-great-grandmothers that now is in production as an eight-part Netflix series starring Octavia Spencer. She is at work on her fifth book, The Joy Goddess of Harlem: A’Lelia Walker and the Harlem Renaissance, a biography of her great-grandmother. Click here to learn more about Madam Walker.

*Breaking it down in even more detail and comparing the value as a commodity and as income or wealth:

COMMODITY

The real price of that commodity is $7,750

The labor value of that commodity is $68,800 for an unskilled worker and $144,000 for a production worker

The income value of that commodity is $161,000

INCOME OR WEALTH

Historic standard of living = $7,750

Economic status = $161,000

Econonic power = $3,150,000

Sometimes writing is like slogging through mud. A vast, clumpy sepia sea that extends beyond the horizon. A molasses thick morass that will be there when the sun goes down and when it comes back up.

Sometimes writing is like slogging through mud. A vast, clumpy sepia sea that extends beyond the horizon. A molasses thick morass that will be there when the sun goes down and when it comes back up.

That’s what the chapter I’m writing right now feels like. Thigh high mud that clutches my feet and ankles. Mud that’s all over my arms and in my hair and in my cuticles.

But I remind myself that the only way to get to a thinner version of the gunk and muck is to keep moving. The only way to get to higher ground and clearer water is to push ahead on the journey.

With each step, the extraneous words and facts get rinsed away. Each time I edit another draft, I’m closer to replacing an amorphous mass with a manicured lawn and a garden of lillies, roses and poppies.

At the moment, I’m not sure how I’m going to get there. The seventy single-spaced pages–22,000 words–that sit in front of me need to be whittled down to half that length. What I thought was one chapter is insisting that it is two. The writing gods have told me I have no control over this. That I was wrong when I thought I could combine these scenes into one chapter.

They have told me that they have been generous enough to lead me to new material–which at first can just look like more mud–and now I must find the gold nugget, polish it and make jewelry! While I think sometimes they’ve sent me off on tangents and wild goose chases, I have learned to trust them. They’ve told me they’re depending on me to use those revelations to tell some stories that have been forgotten and some truths that have been neglected.

And so I slog along with faith that the final draft–the equivalent of a long, warm shower–is worth the effort.

And so I slog along with faith that the final draft–the equivalent of a long, warm shower–is worth the effort.

Anyone who knows me well, knows I’ve been working on a biography of A’Lelia Walker, my great-grandmother and namesake, for more years than I want to admit. After I finished writing On Her Own Ground: The Life and Times of Madam C. J. Walker--the biography of A’Lelia Walker’s mother–I knew her Harlem Renaissance era story called for an additional book so I could chronicle her life and the lives of her intriguing circle of friends through a new lens.

Research for me is mostly fun and exciting. But writing and editing the first and second and twentieth rough draft of a chapter is challenging. Finding the right word and the right rhythm and the right arc are steps in a painstaking process. Getting to the point where the final draft feels ready for an editor’s eyes is satisfying, but much easier said than done.

Langston Hughes and Carl Van Vechten knew A’Lelia Walker and captured her personality more accurately than many others who have written about the Harlem Renaissance.

It’s all been worth it, though. Along the way I’ve discovered that A’Lelia Walker–who is best known as the daughter of entrepreneur Madam C. J. Walker–is very different from the caricature she has become in the minds of many scholars, novelists and playwrights who have written about her during the last three decades. People who actually knew her–contemporaries like Langston Hughes and Carl Van Vechten–captured her well: Van Vechten in an unpublished New Yorker profile, Hughes in the poem he wrote for her funeral and in his memoir, The Big Sea. In recent years, though, she’s been reduced to the first generation/second generation wealth cliche: “Madam made the money. Her daughter spent the money.”

A’Lelia Walker and her mother, Madam C. J. Walker, with their chauffeur in front of Madam Walker’s Indianapolis home, circa 1914. (Madam Walker Family Archives)

There’s no question that A’Lelia Walker enjoyed the wealth, houses and celebrity she inherited when her mother died in 1919. Yes, she spent a lot of money, but she had a lot of money to spend. To reduce her to a spendthrift who frittered away a fortune is to miss the point of what it meant to be the first black heiress. A narrative that claims she singlehandedly decimated the Walker fortune ignores the context of the Great Depression and the effects the stock market crash had on all American businesses. Like most human beings, she’s more complex–and far more interesting–than the simplistic caricature. She was a big spirit with a charismatic personality. A generous soul. A fashion leader who wore furs, turbans, diamonds and custom made shoes. A social impresario who understood the dramatic gesture, whether she was hosting the president of Liberia for a Fourth of July weekend at Villa Lewaro, her Hudson River estate, or orchestrating the extravagant wedding of her daughter, Mae. She could be regal and she could be entirely down to earth. She had bouts of insecurity because her own accomplishments could never measure up to those of her mother. She had major health problems. She was surrounded by friends who loved her, but also had three unhappy marriages.

I don’t think it’s too much to say that her parties helped define the Harlem Renaissance. From the time she moved to Harlem in 1913, an invitation to her beautifully furnished townhouse on 136th Street near Lenox Avenue (now Malcolm X Boulevard) for dinners, dances and recitals seldom was declined. By the time she converted a floor of the house into the legendary Dark Tower in October 1927, she’d been hosting salon-like soirees for more than a decade.

The invitation A’Lelia Walker sent to hundreds of friends when she converted a floor of her 136th Street townhouse into a cultural salon called The Dark Tower in October 1927. (Madam Walker Family Archives)

Through the years, her guests included James Reese Europe, Florence Mills, J. Rosamond Johnson, Bert Williams, Carl Van Vechten, W. E. B. DuBois, James Weldon Johnson, Alberta Hunter, Nora Holt, Lester Walton, Edna Lewis Thomas, Bernia Austin, Paul Poiret, Clarence Darrow and assorted European royalty. A younger generation of writers and artists from Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston and Dorothy West to Countee Cullen, Aaron Douglas and Richard Bruce Nugent also were welcome. Some of these names still are recognizable. Some aren’t. But trust me, they were the boldface names of the times. And I can’t wait to bring them to life for others.

A’Lelia Walker turns out to be much more a patron of the arts than even I knew when I wrote On Her Own Ground: The Life and Times of Madam C. J. Walker. The conventional wisdom is that the Walker philanthropy ended when Madam Walker died. The truth is A’Lelia Walker contributed to many causes and institutions before and after her mother’s death. She spearheaded a campaign for an ambulance for black soldiers during World War I, donated to the Silent Protest Parade against lynching in 1917 and was the leading fundraiser for the Utopia Neighborhood Children’s Center, a building which later housed the 1963 March on Washington planning offices.

When A’Lelia Walker hosted Liberian President C. D. B. King for a Fourth of July weekend at Villa Lewaro, she hired her friend, Ford Dabney, and his Syncopated Orchestra to provide the music. (Document from the Madam Walker Family Archives)

She regularly hired musicians, photographers, modistes, architects and caterers. She invited theater groups to rehearse in her home and a filmmaker to shoot his movies at her estate at no charge. At various times she let a writer, an actress and a singer stay in one of the apartments in her townhouse rent free. Ford Dabney, whose orchestra performed nightly at Florenz Ziegfeld’s Rooftop Garden during the 1910s, was among the many musicians who played for her parties. She commissioned photographers like R. E. Mercer, James Latimer Allen and James Van Der Zee. And of course as president of the Madam C. J. Walker Manufacturing Company, she was a regular advertiser in black newspapers throughout the country.

During the early 1920s she spent five months abroad. In Paris she stayed in a suite at the Hotel Carlton on the Champs-Elysees near the Arc de Triomphe and was invited to a private showing at Cartier. She attended the opera at Covent Garden in London, witnessed the coronation of the Pope in Rome, toured the pyramids in Egypt on camelback and had an audience with Empress Zauditu in Addis Ababa.

In the process of doing the research that has provided all these facts, I’ve started joking that writing biography is a form of insanity. Temporary insanity, I hope, but insanity nonetheless because of the immersion it requires in another time and in another person’s psyche. Learning what makes A’Lelia Walker tick and figuring out as much as possible about the people who were important to her has required a great deal of detective work: Combing through newspaper articles in dozens of digitized databases. Transcribing and annotating thousands of pages of letters and business records. Re-visiting hundreds of files from my research of the last four decades. Reading scores of books on everything from early twentieth century American theater and the history of boxing to World War I black soldiers and Prohibition. I’m never satisfied until I’ve looked under every rock, followed every lead to its end, verified the facts. I’m obsessive about detail. I’m allergic to taking what others have written at face value, even scholars whose work I admire and appreciate. My long career as a journalist makes me want to know not just one primary source and but a verifying second one.

My books are spread all over the house. While I’m writing Joy Goddess, I’ve moved the biographies about A’Lelia Walker’s friends and contemporaries to the bookshelf directly behind my desk. (Photo by A’Lelia Bundles)

When I look on my bookshelves, I’m grateful to all the authors who have written about other Harlem Renaissance figures. In addition to books by A’Lelia Walker’s friends (including Langston Hughes’s The Big Sea, James Weldon Johnson’s Black Manhattan and Carl Van Vechten’s The Splendid, Drunken Twenties), I rely upon dozens of other more recent historical accounts and biographies. To name just a few: Bruce Kellner’s The Harlem Renaissance: A Historical Dictionary for the Era, Emily Bernard’s Remember Me to Harlem, Valerie Boyd’s Wrapped in Rainbows and Hill and Hatch’s A History of African American Theatre. Having their work has provided a welcome road map and countless leads.

The research materials I’ve gathered during the last four decades are organized in thousands of folders. These are some of the files with biographical information of people who knew A’Lelia Walker and Madam Walker.

I often fret about how long it takes me to get each chapter into shape, but there’s too much at stake when writing the first major biography of someone like A’Lelia Walker not to get it right. I can’t claim that she had the creative talent of a Florence Mills or a Langston Hughes, so this is a different kind of biography. More a story of someone who personified her times, who came into contact with just about everybody worth knowing in 1920s Harlem, who provided the setting and atmosphere for the others to be themselves and whom many people wanted to meet. In that sense, it’s a biography of a group of people and the scene they created in a certain place and time. There had never been a such a community of black people with so much talent, so many options, so much potential in such a concentrated few square blocks.

A’Lelia Walker counted among her friends a group of elegant pioneers, talented artists, world-renowned musicians, successful entrepreneurs, global travelers, socialites. Originals who created a parallel world in a nation that didn’t fully appreciate all they had to offer. Sophisticates who transformed their corner of Manhattan into the center of a particularly fascinating universe. She lived from 1885 to 1931, but her legacy was in tact several decades later when old time Harlemites still remembered her parties as the best of a very lively, very culturally exciting, sometimes risque era.

For more about A’Lelia Walker

A’Lelia Walker’s 1924 Visit to Atlantic City

A’Lelia Walker Visits Ethiopian Empress Zauditu

A’Lelia Walker Travels to Europe on the SS Paris

A’Lelia Walker’s Grand 1931 Funeral

When I was a toddler eating dinner with my parents, there was no way for me to know that our silverware — with its “CJW” monogram — would inspire four books, including On Her Own Ground: The Life and Times of Madam C. J. Walker, the biography that provided the factual material for the fictionalized four-part Netflix series.

When I was a toddler eating dinner with my parents, there was no way for me to know that our silverware — with its “CJW” monogram — would inspire four books, including On Her Own Ground: The Life and Times of Madam C. J. Walker, the biography that provided the factual material for the fictionalized four-part Netflix series.

In 1982, Alex Haley, whose fame from the 1976 Roots miniseries still was cresting, approached us about producing a Madam Walker project. For the next several years, Alex was a helpful mentor as I traveled to more than a dozen American cities doing primary source research and interviewing nearly 20 people who had known, worked with or been friends of Madam Walker and A’Lelia Walker.

In 1982, Alex Haley, whose fame from the 1976 Roots miniseries still was cresting, approached us about producing a Madam Walker project. For the next several years, Alex was a helpful mentor as I traveled to more than a dozen American cities doing primary source research and interviewing nearly 20 people who had known, worked with or been friends of Madam Walker and A’Lelia Walker.

Recent Comments