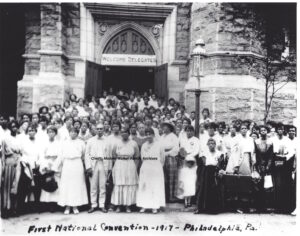

On August 31, 1917, Madam C. J. Walker hosted the first national convention of her Walker “beauty culturists” at Philadelphia’s Union Baptist Church, where a young contralto named Marian Anderson was just beginning to be noticed. More than 200 women from all over the United States gathered to learn about sales, marketing and management at what was one of the earliest professonal gatherings of American women entrepreneurs.

Walker–who founded her Madam C. J. Walker Manufacturing Company during the spring of 1906 in Denver after marrying her third husband, Charles Joseph “C.J.” Walker, earlier that year–had first begun selling hair care products in St.  Louis as an agent for Annie Malone–who was to become her fiercest competitor–around the time of the 1904 World’s Fair. When Walker experienced business conflicts with Malone–and realized that she could improve upon Malone’s products and marketing techniques–she made the decision to establish her own company. Years earlier she had been exposed to the business of hair care by her brothers, who were barbers in St. Louis during the 1880s and 1890s when black men dominated the barbering trade in America.

Louis as an agent for Annie Malone–who was to become her fiercest competitor–around the time of the 1904 World’s Fair. When Walker experienced business conflicts with Malone–and realized that she could improve upon Malone’s products and marketing techniques–she made the decision to establish her own company. Years earlier she had been exposed to the business of hair care by her brothers, who were barbers in St. Louis during the 1880s and 1890s when black men dominated the barbering trade in America.

Madam Walker’s First Ad April 20, 1906 (Madam Walker Family Archives aleliabundles.com)

Between 1906 and 1919, Madam Walker traveled throughout the United States, the Caribbean and Central America training sales agents and promoting her products. In 1916–two years before cosmetics mogul Mary Kay Ash was born–Walker began organizing the women into state and local chapters of the Madam Walker Beauty Culturists League in anticipation of her 1917 convention.

Like Ash, Walker gave prizes and money to the women who had sold the most products and brought in the most new agents. But she also rewarded the women whose chapters had contributed the most to charity in their communities. Walker was determined that her agents use their influence and financial resources to affect political and social change.

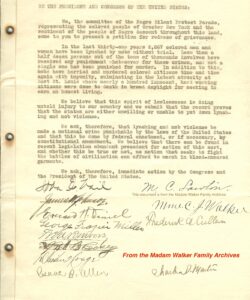

A member of the organizing committee for the NAACP’s July 28, 1917 Silent Protest Parade against lynching, Walker led her convention delegates in sending a telegram to President Woodrow Wilson decrying the East St. Louis riots where at least 39 African Americans had been murdered.

The telegram read: “We, the representatives of the National Convention of the Mme. C. J. Walker Agents, in convention assembled, and in a larger sense representing twelve million Negroes, have keenly felt the injustice done our race and country through the recent lynching at Memphis, Tennessee and the horrible race riot at East St. Louis. Knowing that no people in all the world are more loyal and patriotic than the Colored people of America, we respectfully submit to you this our protest against the continuation of such wrongs and injustices in this ‘land of the free and home of the brave’ and we further respectfully urge that you as President of these United States use your great influence that congress enact the necessary laws to prevent a recurrence of such disgraceful affairs.”

Madam Walker and other Harlem leaders delivered a copy of this petition to the White House/Madam Walker Family Archives (aleliabundles.com)

The next year Walker hosted her second annual convention at Chicago’s Olivet Baptist Church. She died at her home Villa Lewaro in Irvington-on-Hudson, New York on May 25, 1919.

For more information about Walker’s political and business activities, we invite you to read On Her Own Ground: The Life and Times of Madam by Walker’s great-great-granddaughter and biographer, A’Lelia Bundles.

To order a copy, click here. Contact A’Lelia at www.aleliabundles.com.

Learn more about Madam Walker at www.madamcjwalker.com and www.madamwalkerfamilyarchives.wordpress.com

Recent Comments