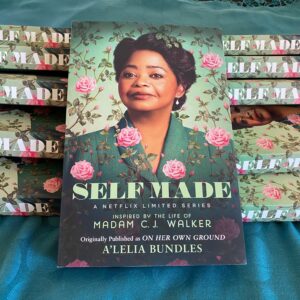

Octavia Spencer as Madam C. J. Walker in “Self Made,” the Netflix series.

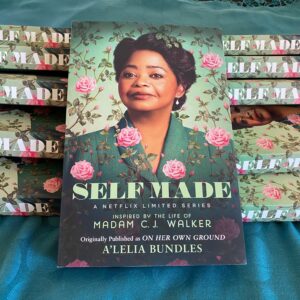

When “Self Made: Inspired by the Life of Madam C. J. Walker” — the Netflix series starring Oscar winner Octavia Spencer — premieres on March 20, millions of people around the world will hear Madam Walker’s name for the first time. Thousands of people, who already know at least a little bit about her, will tune in with hopes of learning something new.

I can tell from the reaction on social media that there’s an audience hungry for a story of black women’s empowerment and African American success. There’s also a core group of Madam Walker fans who wrote elementary school reports about her and cosmetologists who followed in her footsteps. They have been waiting for decades for this particular tale. The excitement reminds me of the 1950s and 1960s when those of us of a certain age ran to our televisions on the rare occasions when a black person appeared on The Ed Sullivan Show or when Nat King Cole finally hosted a show in 1956. Of course, in 2020, we have many other viewing options, but as Walker’s biographer and great-great-granddaughter, I’ve come to know how attached many people feel and how personally they identify with anything related to Madam Walker. It’s wonderful to see so much interest and anticipation. In the last few weeks, I’ve received more than the usual number of speaking engagement requests and noticed the announcements of premiere night viewing parties.

But long before Hollywood came calling, many people recognized the power of Madam Walker’s story and identified with her struggles. The seeds that were planted decades ago are in full bloom. A century after her death, Madam Walker is having a moment.

In 1955, I felt my first moment of Walker magic when I opened my grandmother’s dresser drawer and found miniature mummy charms and receipts from the 1922 trip my great-grandmother, A’Lelia Walker took to Cairo.

I was only three years old and had no idea that that discovery would lead me to write, The Joy Goddess of Harlem: A’Lelia Walker and the Harlem Renaissance, a biography that will be published by Scribner in 2021.

When I was a toddler eating dinner with my parents, there was no way for me to know that our silverware — with its “CJW” monogram — would inspire four books, including On Her Own Ground: The Life and Times of Madam C. J. Walker, the biography that provided the factual material for the fictionalized four-part Netflix series.

When I was a toddler eating dinner with my parents, there was no way for me to know that our silverware — with its “CJW” monogram — would inspire four books, including On Her Own Ground: The Life and Times of Madam C. J. Walker, the biography that provided the factual material for the fictionalized four-part Netflix series.

For the 2020 edition — available for pre-order now! with a publication date of March 24 — I’ve written a new epilogue and made a few revisions. I also recorded an audio book which already is available. The book temporarily has been renamed Self Made to tie in with the series promotion.

There are many events and initiatives during the last 50 years that have set the stage for this moment.

I wrote my first report about A’Lelia Walker in 1970 when I was a senior in high school. As a student at Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism in 1975, I was encouraged by Professor Phyl Garland to write my master’s paper about Madam Walker. At the time, there still was no major biography of Madam Walker or A’Lelia Walker.

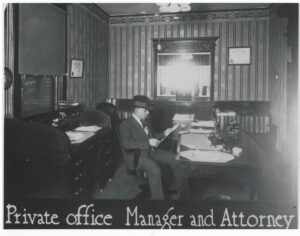

Stanley Nelson’s 1987 “Two Dollars and a Dream,” was the first documentary about Madam Walker. Nelson, whose grandfather Freeman B. Ransom was general manager and general counsel for the Madam C. J. Walker Manufacturing Company, also directed and produced “BOSS: The Black Experience in Business” a 2019 nonfiction film that includes historically accurate information about Madam Walker.

Here’s the transcript and the video.

In 1982, Alex Haley, whose fame from the 1976 Roots miniseries still was cresting, approached us about producing a Madam Walker project. For the next several years, Alex was a helpful mentor as I traveled to more than a dozen American cities doing primary source research and interviewing nearly 20 people who had known, worked with or been friends of Madam Walker and A’Lelia Walker.

In 1982, Alex Haley, whose fame from the 1976 Roots miniseries still was cresting, approached us about producing a Madam Walker project. For the next several years, Alex was a helpful mentor as I traveled to more than a dozen American cities doing primary source research and interviewing nearly 20 people who had known, worked with or been friends of Madam Walker and A’Lelia Walker.

On a freighter trip from Long Beach, California to Guyaquil, Ecuador with Alex and two other writers, I finished the manuscript for Madam C. J. Walker: Entrepreneur, a young adult biography published in 1991.

It’s stunning to think this was the first book length biography of Madam Walker ever published, especially now that my personal library is filled with more than 200 books that chronicle Madam Walker’s life from Tiffany Gill’s Beauty Shop Politics, Noliwe Rooks’s Hair Raising and Kathy Peiss’s Hope in a Jar to Hillary and Chelsea Clinton’s The Book of Gutsy Women, Jean Case’s Be Fearless and The Undefeated’s The Fierce 44.

Madam Walker Books in my personal library

And the scholarship continues. Indiana University professor Tyrone McKinley Freeman’s Madam C. J. Walker’s Gospel of Giving: Black Women’s Philanthropy during Jim Crow will be published in November. Since the 1970s, many people have worked together on a range of initiatives to preserve Madam Walker’s legacy. Among the projects:

a campaign for the 1998 Madam Walker U. S. postage stamp

restoration of the Madam Walker Legacy Center in Indianapolis

designation of Villa Lewaro as a National Trust for Historic Preservation National Treasure

digitization of more than 40,000 items in the Madam Walker Collection at the Indiana Historical Society where a 16 month Madam Walker exhibition — You Are There: Madam Walker 1915 –– opened in September 2019

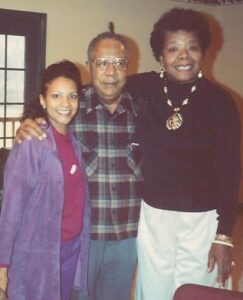

A’Lelia Bundles and Richelieu Dennis, founding CEO of Sundial Brands

renaming of 136th Street at the corner of Malcolm X Boulevard (Lenox Avenue) as Madam C. J. Walker and A’Lelia Walker Place in July 2019

creation of the Madam Walker Family Archives, the largest privately owned collection of Walker records, photographs and memorabilia

dozens of Madam Walker dolls and amazing fine art like Sonya Clark’s large installation at the Austin’s Blanton Museum and Indianapolis’s Alexander Hotel

MCJW, the Madam Walker line of hair care products created by Sundial Brands.

introduction of MCJW, a new line of Madam Walker hair care products manufactured by Sundial Brands and sold exclusively at Sephora.

So, yes, the Netflix series will introduce Madam Walker to many people who otherwise would never have known about her. After you’ve watched the Hollywood version — where the writers have used a great deal of creative license to heighten the drama with characters who didn’t exist and scenes that didn’t occur in real life — we hope you will become curious enough to seek the facts. And of course we hope you will make your way to the new edition of On Her Own Ground as well as some of the blogs about Madam Walker and A’Lelia Walker on this website. There’s also a new audio book that I recorded a few weeks ago.

For updates on all our Madam Walker projects, please visit our Madam Walker Website and follow us on Twitter and Instagram. Click here to sign up for our newsletter.

Professor Tyrone McKinley Freeman, who teaches at Indiana University’s Lilly Family School of Philanthropy, has described the impulse to compare the fortunes of Madam C. J. Walker (1867 – 1919) and Annie Malone (1877* – 1957) as “the first millionaire sweepstakes.” In my observation, this “who was first?” battle has become petty, contrived and counterproductive.

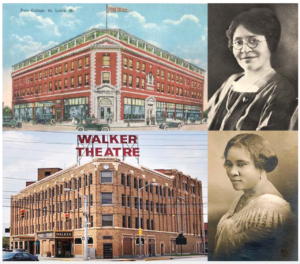

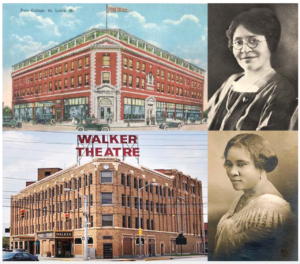

Poro and Walker Building

For a variety of reasons, the now century old rivalry between Madam Walker and Annie Pope-Turnbo Malone continues posthumously with people taking sides in unresolved battles on social media. Most of the time, I try to stay on the sidelines because I long ago learned that it is impossible to change the mind of someone who has no interest in looking at facts and documentation. But for those of you who are open to considering facts, I offer the following information:

There’s no doubt in my mind that Madam C. J. Walker and Annie Malone both are important historical figures who made major contributions as early twentieth century hair care industry pioneers and philanthropists. It is true that Madam Walker sold Malone’s Poro products in St. Louis and in Denver in 1905 and 1906 before marrying Charles Joseph “C.J.” Walker and starting her own Madam C. J. Walker Manufacturing Company. It’s also true that Walker was first introduced to the hair care business in the 1890s by her brothers, who were barbers in St. Louis. As well, it is true that neither Annie Malone or Madam Walker was the first to discover the system of cleansing one’s scalp, then applying a thick ointment that was the consistency of Vaseline — with sulfur as the medicinal agent — to heal the severe scalp infections that were rampant in the early 1900s. It was a time when hygiene was quite different because most Americans lacked in door plumbing. In fact, the remedy they both used had been around for centuries. The basic recipe appears in medical texts as early as the 1700s and was used in other products including Cuticura as well as those manufactured by other black-owned companies during the 1800s. As amazing as both women were, neither was the first to manufacture hair care products for black women. Just a little bit of thought makes it clear that black women had been styling their hair since ancient times.

As a long time journalist and as a biographer who writes non-fiction (i.e. FACT-based) books, I also believe it is important to document one’s assertions and to present accurate information…even on social media where myths and misinformation abound.

Much of the primary source research about the relationship between Walker and Malone first appeared in my book, On Her Own Ground: The Life and Times of Madam C. J. Walker (Scribner, 2001). I was careful to include citations for the newspaper articles and correspondence that documented my assertions in very detailed endnotes. More recently, I wrote a blog post “Madam Walker’s Mentors, Sister Friends and Rivals” that adds to the information about Walker and Malone, as well as the women to whom Walker was close, like St. Louis school teacher Jessie Batts Robinson and anti-lynching activist Ida B. Wells.

Madam C. J. Walker (Credit: Madam Walker Family Archives)

SALES FIGURES FOR MADAM WALKER AND ANNIE MALONE: Since the publication of On Her Own Ground, other authors have written books and articles about Annie Malone. A few years ago, I began to notice “$14 million” as a claim for Malone’s net worth, first in Neema Barnette’s mini-doc video about Malone and then in articles and on social media posts. In 2018, Shomari Wills made the same claim in his book, Black Fortunes: The Story of the First Six African Americans Who Escaped Slavery and Became Millionaires, a poorly researched and error-filled book that had to be revised by his publisher because of the easily found mistakes. For reasons that elude me, he distorted the details of Madam Walker’s life and entirely upended the facts of her appearance and impact at the 1912 National Negro Business League convention.

Because that “$14 million” figure that Wills and others used was new to me, I did additional research to try to learn the origin of the claim. In addition to research I had been gathering for more than 40 years about Walker and Malone, I did an extensive survey of historical newspaper databases on Newspapers.com, Proquest and Genealogybank.com, which now include dozens of black newspapers from the late 1800s and early 1900s.

The first time I was able to find a reference to the $14 million figure was in a 1957 Chicago Defender obituary (“Annie T. Malone Rites at Bethel,” Chicago Defender, May 15, 1957), which read: “Once regarded as the world’s richest Negro woman, her wealth at the peak of her career in the 1920s was estimated at $14 million.”

Two weeks later, the Defender repeated the $14 million figure in another article “How Annie Malone Made, Lost a Fortune.”

In December 1962, the Defender again repeated the $14 million figure.

Annie Malone

But no documentation or business records for this claim were cited in the articles and the figure had never appeared in newspaper reports prior to Malone’s death in 1957. Without such documentation or prior contemporaneous reporting during Malone’s lifetime, the figure seems to be drawn from thin air.

Just as misinformation goes viral today, it seems to have gone viral in 1957 and then to have been resurrected in 2020.

When On Her Own Ground first was published in 2001, I estimated Madam Walker’s personal wealth (homes, real estate investments, jewelry, cars, clothing, furniture, etc) to be between $600,000 and $700,000. However, a business historian pointed out to me a year later that I had failed to include the value of Madam Walker’s company in my estimation of her wealth. When one takes into account the sales for the last two years of her life and the year following her death, I was advised that the value of her company, had it been sold on the day of her death, would have been between $1 million and $2 million in 1919 dollars.

Here are the gross receipts for 1918 – 1920 (as documented in Walker Company annual reports and tax records in our Madam Walker Family Archives and in the Walker Collection at the Indiana Historical Society):

1918 earnings: $275,937.88 (an increase of $100,000 from 1917)

1919 earnings $486,762

1920 earnings: $595,353 (or $9,272,135.87 in 2020 according to Dollar Times Calculator)

We are fortunate that we can document Madam Walker’s sales because of the voluminous records that were preserved from the Madam C. J. Walker Manufacturing Company. Unfortunately, similar documentation does not exist for the Poro Company. Unless such records surface, there is no way to prove the claims about Malone’s wealth.

During the last four decades, I’ve created a file of hundreds of articles that mention Malone or Poro between 1903 and the time of her death in 1957. Some of those articles quote officials of the Poro Company regarding the claims for annual sales and company value. I have not found any articles prior to Madam Walker’s death in 1919 or Annie Malone’s death in 1957 that claimed that Malone was “worth $14 million.”

Instead I have found the following:

In November 1913 the Cleveland Gazette, where Annie (then Pope-Turnbo) frequently advertised, the Doings of the Race columnist wrote, “An expert going over the books found the receipts from the sale of hair preparations and agents fees total from $100 to $150 per day.” The Chicago Defender also carried a story giving the $100 to $150 per day” figure.

That $100 to $150 per day would be between $36,500 and $54,750 annually if received seven days a week or between $26,100 and $39,150 annually based on Monday through Friday receipts.

In August 1915, in response to a law suit brought by Walter Majors (a former Malone business partner who sued her for reneging on a share of the 1913 profits she had promised him), a report of the earnings of the previous 33 months was $63,650.03 gross with $24,333.60 net. Another article says the period was “fourteen months” with a “monthly net profit of $1,738.” (14 x $1,738 = $24,333.60).

1918: “A $50,000 Corporation with $250,000 Yearly Business…From last year’s statistics, presented [to] the Bee reporter, is shown in round numbers $250,000 business done.” (“Notable Career of Prof. and Mrs. A.E. Malone,” Washington Bee, August 31, 1918) [Walker’s gross receipts that year, as documented in the annual report prepared by her attorney, were $275,937.88.]

1924: In November, the Topeka Plaindealer reported that Malone had “paid $38,408 income tax for 1923. Her business represents an investment of $750,000.” (“She Is Solving the Race Question,” Plaindealer (Topeka, KS), November 14, 1924)

1926 “Mrs. Malone is probably the Race’s leading business woman and is known to be worth several millions of dollars.” [though I will point out that this reporter cites no documentation] (“Former Banker’s Home Brings Nearly $50,000,” Philadelphia Tribune, Jan 30, 1926)

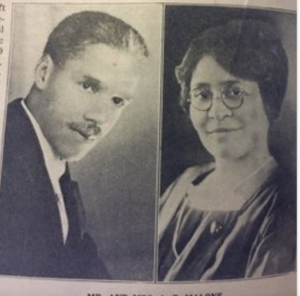

Aaron Malone and Annie Pope Turnbo married in 1914

WHY IS MADAM WALKER MORE WELL-KNOWN THAN ANNIE MALONE: There are many possible reasons why Madam Walker is more well-known today than Annie Malone. Madam Walker died at the height of her fame in May 1919 with her wealth intact while Malone experienced business and reputational setbacks during the 1920s after a contentious divorce from Aaron Malone, who worked to turn some of her employees against her and to undermine her leadership role.

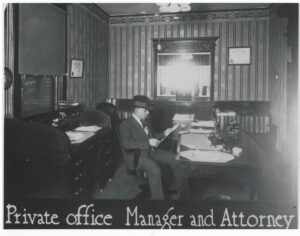

Madam Walker had a knack for hiring and empowering strong leaders who enhanced her company. Her carefully selected executive team included Freeman B. Ransom, the attorney who guarded against legal threats, while Malone was involved in a decades long lawsuit brought by Walter Majors, a former business partner, who accused her of failing to pay a portion of profits promised to him in 1913. (Among the articles that document this legal battle is “Referee Finds Against Beauty Specialist,” Indianapolis Freeman, August 28, 1915.)

Madam C. J. Walker Mfg. Co. Atty F. B. Ransom circa 1912 (Madam Walker Family Archives)

While Attorney Ransom steadfastly paid Madam Walker’s personal and corporate federal income taxes, Malone disputed her federal tax assessment and faced a large unpaid federal tax bill during the 1940s.

Madam Walker’s secretary Violet Davis Reynolds, who worked for the Walker Company from 1914 until 1979, kept meticulous records and preserved thousands of Walker’s personal letters and financial documents, which are housed at the Indiana Historical Society. There is no comparable body of records for Annie Malone or the Poro Company.

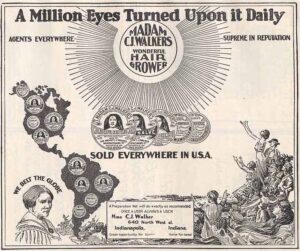

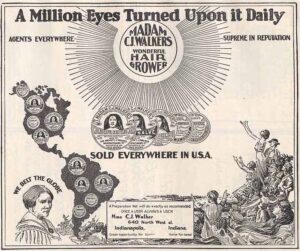

Madam Walker advertised heavily in the black press and cultivated relationships with black editors and publishers. Like her contemporaries Helena Rubinstein and Elizabeth Arden, she created national distribution platforms for her products. She traveled to the Caribbean and Central America in 1913 to expand her market internationally.

Madam Walker advertised in dozens of black newspapers.

Another factor may be her daughter A’Lelia Walker’s suggestion that they establish a presence in Harlem in 1913 just as this uptown Manhattan neighborhood was becoming a political and cultural mecca for African Americans. A’Lelia Walker operated the Walker Beauty School and Salon in Harlem, then converted a floor of their 136th Street townhouse into The Dark Tower, which became an iconic gathering place for the artists, writers, musicians, actors and celebrities of the Harlem Renaissance.

By the mid-1970s most of the Poro and Walker Beauty Schools had closed. I have not been able to determine when the Poro Company stopped manufacturing its line of hair care products. The Madam C. J. Walker Manufacturing Company never went out of business. The trademark was sold by the Madam Walker trustees in the early 1980s to an entity that manufactured some of the original formulas for the next three decades.

MADAM by Madam C. J. Walker at Walmart

In 2013 Richelieu Dennis, founder of Sundial Brands, acquired the Walker trademark for cosmetics and hair care products and revived the line with all new formulas. Today the MCJW line is sold exclusively at Walmart stores and at Walmart.com.

Madam Walker’s legacy also benefits from two very tangible reminders. The Madam Walker Legacy Center in Indianapolis is a National Historic Landmark. Villa Lewaro, the mansion designed by architect Vertner Tandy (a founder of Alpha Phi Alpha), is both a National Historic Landmark and one of the National Trust for Historic Preservation’s designated National Treasures.

Villa Lewaro, estate of Madam C. J. Walker, 1924 (Madam Walker Family Archives0

So who was first? Madam Walker or Annie Malone? If you’ve made it this far in the article, you know that Madam Walker’s wealth can be documented while Annie Malone’s can not. My personal perspective is that Madam Walker’s legacy is measured more in the jobs she created, the philanthropy she dispensed, the lives she changed and the seeds she planted for political activism than in whether she was “the first self-made American woman millionaire,” as the Guinness Book of World Records states.

So those who want to keep arguing this point can have at it.

If you’re interested in learning more about Madam Walker and what’s truly important about her legacy, we urge you to read the new edition of On Her Own Ground: The Life and Times of Madam C. J. Walker or listen to the audio book that I recently recorded. If you happen to be in Indianapolis, we hope you’ll visit the Madam Walker Legacy Center and the Indiana Historical Society where a major exhibit — “You Are There: Madam Walker 1915 Empowering Women” — is up until January 2021.

*Malone was born in 1877. This is a correction.

Madam C. J. Walker was born 150 years ago on December 23, 1867.

Madam C. J. Walker was born Sarah Breedlove on December 23, 1867 on the same Delta, Louisiana plantation where her parents and older siblings had been enslaved before the Civil War.

Orphaned at seven and a poorly paid washerwoman in St. Louis until she was 38 years old, she had become America’s wealthiest self-made businesswoman by the time of her death in 1919.

Walker was known as an entreprenuer, hair care industry pioneer, philanthropist, patron of the arts and political activist. From her company headquarters in Indianapolis, she provided jobs and economic independence for thousands of African American women. She began to develope an international sales force in 1913 when she visited Cuba, Jamaica, Haiti, Costa Rica and Panama.

In August 1917, she hosted one of the first large national conventions for women entrepreneurs. In May 1919, her $5,000 gift to the NAACP’s anti-lynching fund was the largest charitable contribution the organization had ever received at the time. She supported the careers of many notable African American musicians and artists.

When she died at Villa Lewaro, her Irvington, New York estate on May 25, 1919, she left more than $100,000 to African American schools, organizations and institutions.

Among the many ways her legacy still lives

For more information about Madam Walker visit www.madamcjwalker.com and www.mcjwbeautyculture.com

Biographies of Walker by A’Lelia Bundles

- On Her Own Ground: The Life and Times of Madam C. J. Walker (Scribner/Washington Square Press)

- All about Madam C. J. Walker (Cardinal Publishing)

- Madam Walker Theatre Center: An Indianapolis Treasure (Arcadia)

- Madam C. J. Walker: Entrepreneur (Chelsea House)

Today — December 23, 2015 — is the 148th anniversary of Madam C. J. Walker’s birth!

She was born Sarah Breedlove on December 23, 1867 in Delta, Louisiana on the same planation where her parents Owen and Minerva Anderson Breedlove had been enslaved. The first child in her family to be born after the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863, her birth was greeted with much hope and promise. But the Breedlove family’s reality was bleak.

By the time Sarah was seven years old, both parents had died. At ten, she moved across the Mississippi River to Vicksburg, Mississippi with her older sister, Louvenia, and her brother-in-law, Jesse Powell, who was so cruel, she would later say, that she “married at 14 to get a home of my own.” Another blow came with the death of her husband, Moses McWilliams, when she was 20. Now with her two-year old daughter, Lelia (later known as A’Lelia Walker) to raise, she moved up the river to St. Louis, Missouri where her older brothers worked as barbers.

She struggled for the next decade working as a laundress, doing the back-breaking work of washing clothes by hand in tubs and without indoor plumbing. At the end of some weeks, she’d made as little as $1.50, but her dreams for her daughter made her persevere. One day while her hands were buried deep in soap suds, she despaired that life might never get better. But the solution to her problems eventually came when she developed a shampoo and ointment to heal the scalp disease that was causing her to go bald.

Madam Walker died at Villa Lewaro in May 1919.

By the time she died on May 25, 1919 at Villa Lewaro (her mansion in Irvington-on-Hudson, New York), she had founded the Madam C. J. Walker Manufacturing Company and become a millionaire, some say the first self-made American woman to attain that level of financial success.

There is much more to her story of course. How she discovered, developed and marketed her “Wonderful Hair Grower.” How she employed thousands of women as Walker sales agents and beauty culturists. How she spoke up to Booker T. Washington at his 1912 National Negro Business League Convention. How she gathered more than 200 women together for one of America’s first national conventions of women entrepreneurs in 1917. Her prominence as a philanthropist and patron of the arts. Her friendships with Ida B. Wells, W.E.B. DuBois, Mary McLeod Bethune and James Weldon Johnson among others. Her $1,000 contribution to Indianapolis’s YMCA and $5,000 to the NAACP’s anti-lynching campaign. Her activism on behalf of black soldiers, young women and the rights of African Americans.

Her legacy of entrepreneurship and philanthropy still empowers others. She is often mentioned by businesswomen in America and beyond as an inspiration. Her company is discussed and critiqued in a Harvard Business School course. Dozens of students across the nation prepare projects about her every year for National History Day. Countless young girls have dressed up as Madam Walker for Black History Month and Women’s History Month. She is the subject of numerous documentaries, public service announcements and news stories. Several organizations host annual Madam Walker awards luncheons. The Madam Walker Collection of photographs, letters and business records is the most popular collection at the Indiana Historical Society. She was featured on a U. S. postage stamp in 1998. Recently her name was touted as contender for the $20 bill. There are two National Historic Landmarks associated with her life: Villa Lewaro in Irvington-on-Hudson, New York and the Madam Walker Theatre Center in Indianapolis, Indiana.

Here are some of the books in which she has been featured or mentioned in the last couple of years.

Angella M. Nazarian’s Visionary Women (Assouline Publishers)

Cynthia L. Greene’s Entrepreneurship: Ideas in Action (Cengage Learning)

Faith Ringgold’s Harlem Renaissance Party (Amistad)

James J. Madison and Lee Ann Sandweiss’s Hoosiers and the American Story (Indiana Historical Society)

Martin Kilson’s Transformation of the African American Intelligentsia 1880 – 2012 (Harvard University Press)

Diane Radmacher’s Famous Firsts of St. Louis: A Celebration of Facts, Figures, Food & Fun

As we approach the 150th anniversary of her birth, we can say there are more exciting announcements to come in the new year. Stay tuned!

Other blog posts that might interest you

A Family Perspective: Celebrating Madam Walker’s Legacy

Madam Walker’s 1917 Convention: Entrepreneurship and Protest Politics

Madam Walker’s Mansion: The Future of Villa Lewaro

Madam Walker’s August Garden

Woodlawn Cemetery — Burial Place of Madam Walker — Designated National Historic Landmark

Madam Walker Visits the Brothers Dumas in Mississippi

Madam Walker Black History Month 2013

To learn more about Madam Walker, visit our official Madam C. J. Walker website at www.madamcjwalker.com

To order On Her Own Ground: The Life and Times of Madam C. J. Walker and Madam Walker Theatre Center, visit my website at www.aleliabundles.com

Here’s a link to videos about Madam Walker.

Check out Madam Walker on Facebook.

During the week of October 19, 2014 the National Trust for Historic Preservation featured Villa Lewaro, Madam Walker’s Irvington-on-Hudson, New York estate, on all its social media platforms. This piece that I wrote for the Trust’s Preservation Blog also appeared on Huffington Post and Jet.com

Inside Villa Lewaro, Madam C. J. Walker’s Irvington-on-Hudson, NY mansion (David Bohl/Historic New England)

Every time I walk through the doors of Villa Lewaro—the mansion my great-great-grandmother, Madam C. J. Walker, called her “dream of dreams”—I always take a moment to imagine the pride and magic the ancestors must have felt in these rooms. From the columns of the majestic portico to the balustrades of the grand terrace, the original stucco façade sparkled with marble dust and glistening grains of white sand when the laundress-turned-millionaire took possession in May 1918.

Villa Lewaro 1920s

The New York Times pronounced it “a place fit for a fairy princess.” Enrico Caruso, the world famous opera tenor, was so entranced by its similarity to estates in his native Naples that he coined the name “Lewaro” in honor of A’Lelia Walker Robinson, Madam Walker’s only daughter.

Walker told her friend Ida B. Wells, the journalist and anti-lynching activist, that after working so hard all her life—first as a farm laborer, then as a maid and a cook, and finally as the founder of an international hair care enterprise—she wanted a place to relax and garden and entertain her friends.

She also wanted to make a statement, so it was no accident that she purchased four and a half acres in Irvington-on-Hudson, New York not far from Jay Gould’s Lyndhurst and John D. Rockefeller’s Kykuit amidst America’s wealthiest families. She directed Vertner Woodson Tandy—the black architect who already had designed her opulent Harlem townhouse—to position the 34-room mansion close to the village’s main thoroughfare so it was easily visible by travelers en route from Manhattan to Albany.

Villa Lewaro Aerial (Courtesy Madam Walker Family Archives)

Indeed, the Times reported that her new neighbors were “puzzled” and “gasped in astonishment” when they learned that a black woman was the owner. “Impossible!” they exclaimed. “No woman of her race could afford such a place.”

The woman born in 1867 in a dim Louisiana sharecropper’s cabin on the banks of the Mississippi River, now awoke each morning in a sunny master suite with a view of the Hudson River and the New Jersey Palisades. The child who had crawled on dirt floors now walked on carpets of Persian silk. The destitute washerwoman, who had lived across the alley from the St. Louis bar where Scott Joplin composed ragtime tunes, now hosted private concerts beneath shimmering chandeliers in her gold music room.

But the home was not constructed merely for her personal pleasure. Villa Lewaro, she hoped, would inspire young African Americans to “do big things” and to see “what can be accomplished by thrift, industry and intelligent investment of money.”

“Do not fail to mention that the Irvington home, after my death, will be left to some cause that will be beneficial to the race—a sort of monument,” she instructed her attorney, F. B. Ransom. As the largest contributor to the fund that saved Frederick Douglass’s Anacostia home, Cedar Hill, she understood the importance of preservation as a strategy to claim and influence history’s narrative.

Invitation to the August 1918 Villa Lewaro gathering honoring Emmett Scott (Courtesy Madam Walker Family Archives)

For her opening gathering in August 1918, Madam Walker honored Emmett Scott, then the Special Assistant to the U. S. Secretary of War in Charge of Negro Affairs and the highest ranking African American in the federal government. At this “conference of interest to the race”—with its Who’s Who of black Americans and progressive whites—she encouraged discussion and debate about civil rights, lynching, racial discrimination and the status of black soldiers then serving in France during World War I. After a weekend of conversation, collegiality and music provided by J. Rosamond Johnson—co-composer of “Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing”—and Joseph Douglass, master violinist and grandson of Frederick Douglass, Scott wrote to her, “No such assemblage has ever gathered at the private home of any representative of our race, I am sure.”

After Madam Walker died at Villa Lewaro on May 25, 1919—barely a year after moving in—her daughter continued the tradition of hosting events, occasionally opening the home for public tours to honor Walker’s legacy. Later dubbed the “joy goddess of Harlem’s 1920s” by poet Langston Hughes because of her impressive soirees, A’Lelia Walker feted Liberian President Charles D. B. King and his entourage in 1921 with a Fourth of July fireworks display and concert by the Ford Dabney Orchestra. In November 1923, limousines lined Broadway as several hundred bejeweled and fancily dressed wedding reception guests arrived from Harlem’s St. Philips Episcopal Church where my grandmother Mae had married her first husband, Dr. Gordon Jackson. The following summer, more than 400 sales agents and cosmetologists journeyed from all over the United States and the Caribbean for the eighth annual convention of the Madam Walker Beauty Culturists Union.

A’Lelia Walker in Villa Lewaro’s Music Room (Courtesy of Madam Walker Familly Archives)

In the late 1970s, as I was beginning to research the Walker women’s lives, I made my first visit to the house. Sold soon after A’Lelia Walker’s death in 1931 in the midst of the Great Depression, it had been a retirement home for elderly white women for several decades. Even with its beauty then obscured and its furnishings meager, I still could see the lingering grandeur in the hand-painted murals and the marble stairs. When I interviewed blues legend Alberta Hunter a few years later, she told tales of elegant weekend parties and of playing the Estey organ as she gently awakened the other guests.

Through the years I’ve watched as ownership has moved from the Companions of the Forest to Ingo and Darlene Appel and then to Harold and Helena Doley. They all have been stewards in their own caring way. For more than two decades, the Doleys have invested considerable resources and patience to restore the home and the grounds, even hosting a designer show house benefitting the United Negro College Fund in 1998.

In May 1922 the National Trust for Historic Preservation and the Rockefellers Brothers Fund hosted a gathering of preservationists, developers and entrepreneurs to discuss the future of Villa Lewaro.

Among the earliest and most notable mansions built and owned by an African American and by an American woman entrepreneur, Villa Lewaro is one of the few remaining tangible symbols of the astonishing progress made by the generation born just after Emancipation and the Civil War. Without this evidence, our history can be intentionally misinterpreted and easily dismissed. Having walls to touch and doors to open helps our children and grandchildren verify the ancestors’ accomplishments and connect themselves to their rich heritage.

It is vital that we work to find ways to imagine Villa Lewaro’s future so that it can continue to inspire others and to be, as Madam Walker dreamed “a monument to brains, hustle and energy…and a mile stone in the history of a race’s advancement.”

To support these efforts, please click here to sign the pledge to preserve Madam Walker’s Villa Lewaro and here to make a monetary donation through the National Trust.

A’Lelia Bundles is Walker’s great-great-granddaughter and author of On Her Own Ground: The Life and Times of Madam C. J. Walker. Her website is www.aleliabundles.com

When I was a toddler eating dinner with my parents, there was no way for me to know that our silverware — with its “CJW” monogram — would inspire four books, including On Her Own Ground: The Life and Times of Madam C. J. Walker, the biography that provided the factual material for the fictionalized four-part Netflix series.

When I was a toddler eating dinner with my parents, there was no way for me to know that our silverware — with its “CJW” monogram — would inspire four books, including On Her Own Ground: The Life and Times of Madam C. J. Walker, the biography that provided the factual material for the fictionalized four-part Netflix series.

In 1982, Alex Haley, whose fame from the 1976 Roots miniseries still was cresting, approached us about producing a Madam Walker project. For the next several years, Alex was a helpful mentor as I traveled to more than a dozen American cities doing primary source research and interviewing nearly 20 people who had known, worked with or been friends of Madam Walker and A’Lelia Walker.

In 1982, Alex Haley, whose fame from the 1976 Roots miniseries still was cresting, approached us about producing a Madam Walker project. For the next several years, Alex was a helpful mentor as I traveled to more than a dozen American cities doing primary source research and interviewing nearly 20 people who had known, worked with or been friends of Madam Walker and A’Lelia Walker.

Recent Comments