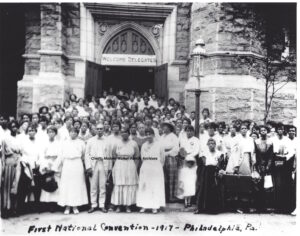

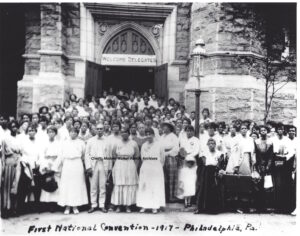

One hundred years ago this week — on August 30 and August 31, 1917 — hair care entrepreneur Madam C. J. Walker hosted the first annual convention of her sales agents and beauty culturists. More than 200 women gathered at Philadelphia’s Union Baptist Church to hear Walker’s message about entrepreneurship, civic responsibility and political activism.

At one of the first conventions of American businesswomen, the delegates shared stories of how their work as Walker agents had transformed and enriched their lives.

With few career opportunities open to black women during the early twentieth century, many had been maids, washerwomen, cooks and sharecroppers. A few had been teachers and nurses. Now they talked of the financial rewards that allowed them to purchase homes, educate their children and contribute to their churches and community organizations.

1917 Convention of Madam Walker agents in Philadelphia (Madam Walker Family Archives)

Margaret Thompson, president of the Philadelphia Union of Walker Hair Culturists told her colleagues that she had earned $5 a week as a servant. Now she claimed an income of $250 a week (the equivalent of more than $5,200 in 2017 dollars).

On the final day of the convention Madam Walker’s theme was “Women’s Duty to Women.” She envisioned these economically successful women as community leaders and agents of change. To emphasize the point, she gave $500 in prizes, not only to the women who had sold the most tins of Madam Walker’s Wonderful Hair Grower, but to those whose local Walker clubs had contributed the most to charity.

At the end of the convention, the women sent a telegram to President Woodrow Wilson urging him to support legislation that would make lynching a federal crime.

“We, the representatives of the National Convention of the Madam C. J. Walker Agents, in convention assembled, and in a larger sense representing twelve million Negroes, have keenly felt the injustice done our race and country through the recent lynching at Memphis, Tennessee, and the horrible race riot at East St. Louis.”

“Knowing that no people in all the world are more loyal and patriotic than the Colored people of America, we respectfully submit to you this our protest against the continuation of such wrongs and injustices in this ‘land of the free and the home of the brave’ and we further respectfully urge that you as President of these United States use your great influence that Congress enact the necessary laws to prevent a recurrence of such disgraceful affairs.”

The Madam C. J. Walker Manufacturing Company continued a tradition of annual conventions through the early 1960s.

Today the Madam C. J. Walker Beauty Culture line of hair care products is manufactured by Sundial Brands and sold nationwide at Sephora.Madam C. J. Walker Beauty Culture (mcjwbeautyculture.com)

July 28 marked the 100th anniversary of the Silent Protest Parade when 10,000 African Americans of all ages marched silently up Fifth Avenue to protest lynchings in America. As they stepped solemnly past thousands of onlookers, the only sounds were the muffled tat-a-tat of a drum and the scrape of shoes across pavement.

Men, women and 800 children had gathered to declare their outrage over the May 15 lynching of 17-year old Jesse Washington in Waco, Texas and the July 2 riot in East St. Louis, Illinois where white mobs murdered more than three dozen African Americans and attacked hundreds.

Silent Protest Parade July 28, 1917 (NYPL Digital Collection)

Today marks another important date related to that demonstration of defiance. On August 1, 1917 members of the NAACP’s New York chapter executive committee traveled from Harlem to Washington, DC to lobby President Woodrow Wilson for support of legislation to make lynching a federal crime.

The group was led by NAACP field secretary James Weldon Johnson and included entrepreneur Madam C. J. Walker, realtor John Nail, New York Age publisher Fred Moore and Rev. Frederick Cullen. They had been assured of a noon meeting with Wilson, but when they arrived at the White House, they were told he was occupied with other matters. Wilson, who had praised D. W. Griffith’s racist movie, “Birth of a Nation,” and instituted segregation in federal offices, had long displayed his disdain for African Americans and their concerns.

Anti-lynching petition delivered to the White House on August 1, 1917 after the Silent Protest Parade in New York. (Credit: Madam Walker Family Archives)

The delegation presented the petition to Wilson’s secretary, Joseph Tumulty, then traveled up Pennsylvania Avenue to Capitol Hill where they met with the few members of Congress who were receptive to their cause. Several months later Congressman Leonidas Dyer — whose St. Louis district was just across the Mississippi River from East St. Louis — introduced a bill that would have required the crime of lynching to be tried in federal court as capital murder. The Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill was passed by the U.S. House of Representatives on January 26, 1922, but was blocked by a Southern Democratic filibuster in the U.S. Senate and never brought to vote.

Beginning in 1882, more than 200 anti-lynching bills were introduced in Congress, but to this day not one has been enacted. In 2005, 80 U.S. Senators approved a resolution apologizing for the U. S. government’s failure to enact this legislation. But it was an apology and not a law.

Even in the 21st Century, there was insufficient will to declare that #BlackLivesMatter.

John Shillady Letter to Madam Walker on May 10, 1919 (Credit: Madam Walker Family Archives)

The NAACP continued its campaign against lynching. During a mass meeting at Carnegie Hall in May 1919, Madam Walker pledged $5,000 to the anti-lynching fund. In his May 10, 1919 letter to Walker, NAACP secretary John R. Shillady noted that it was “the largest [gift] the Association has ever received.”

For more information about the Silent Protest Parade:

Equal Justice Insitute: “A Century after the Silent Protest Parade, Racial Injustice Persists” (July 28, 2017)

Beinecke Library Display July 2017

Black Americans in Congress: “Anti-Lynching Legislation Renewed”

On Her Own Ground: The Life and Times of Madam C. J. Walker by A’Lelia Bundles (pp 203-217)

Recent Comments