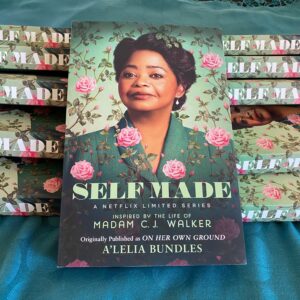

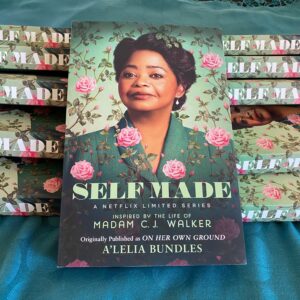

Octavia Spencer as Madam C. J. Walker in “Self Made,” the Netflix series.

When “Self Made: Inspired by the Life of Madam C. J. Walker” — the Netflix series starring Oscar winner Octavia Spencer — premieres on March 20, millions of people around the world will hear Madam Walker’s name for the first time. Thousands of people, who already know at least a little bit about her, will tune in with hopes of learning something new.

I can tell from the reaction on social media that there’s an audience hungry for a story of black women’s empowerment and African American success. There’s also a core group of Madam Walker fans who wrote elementary school reports about her and cosmetologists who followed in her footsteps. They have been waiting for decades for this particular tale. The excitement reminds me of the 1950s and 1960s when those of us of a certain age ran to our televisions on the rare occasions when a black person appeared on The Ed Sullivan Show or when Nat King Cole finally hosted a show in 1956. Of course, in 2020, we have many other viewing options, but as Walker’s biographer and great-great-granddaughter, I’ve come to know how attached many people feel and how personally they identify with anything related to Madam Walker. It’s wonderful to see so much interest and anticipation. In the last few weeks, I’ve received more than the usual number of speaking engagement requests and noticed the announcements of premiere night viewing parties.

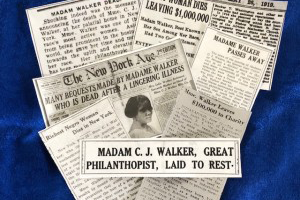

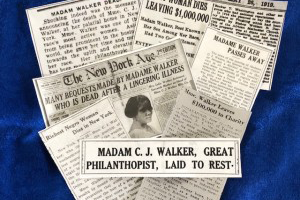

But long before Hollywood came calling, many people recognized the power of Madam Walker’s story and identified with her struggles. The seeds that were planted decades ago are in full bloom. A century after her death, Madam Walker is having a moment.

In 1955, I felt my first moment of Walker magic when I opened my grandmother’s dresser drawer and found miniature mummy charms and receipts from the 1922 trip my great-grandmother, A’Lelia Walker took to Cairo.

I was only three years old and had no idea that that discovery would lead me to write, The Joy Goddess of Harlem: A’Lelia Walker and the Harlem Renaissance, a biography that will be published by Scribner in 2021.

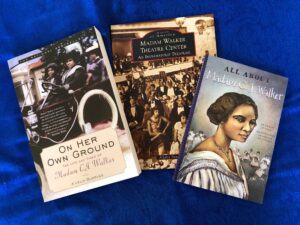

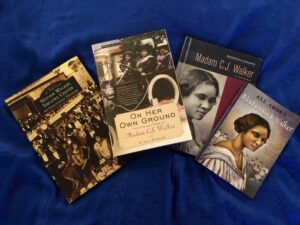

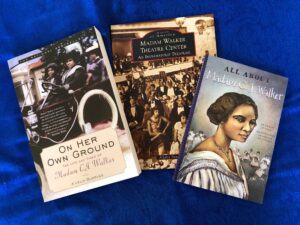

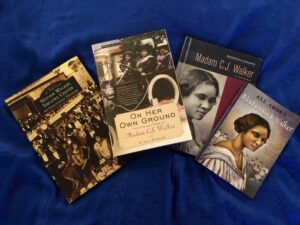

When I was a toddler eating dinner with my parents, there was no way for me to know that our silverware — with its “CJW” monogram — would inspire four books, including On Her Own Ground: The Life and Times of Madam C. J. Walker, the biography that provided the factual material for the fictionalized four-part Netflix series.

When I was a toddler eating dinner with my parents, there was no way for me to know that our silverware — with its “CJW” monogram — would inspire four books, including On Her Own Ground: The Life and Times of Madam C. J. Walker, the biography that provided the factual material for the fictionalized four-part Netflix series.

For the 2020 edition — available for pre-order now! with a publication date of March 24 — I’ve written a new epilogue and made a few revisions. I also recorded an audio book which already is available. The book temporarily has been renamed Self Made to tie in with the series promotion.

There are many events and initiatives during the last 50 years that have set the stage for this moment.

I wrote my first report about A’Lelia Walker in 1970 when I was a senior in high school. As a student at Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism in 1975, I was encouraged by Professor Phyl Garland to write my master’s paper about Madam Walker. At the time, there still was no major biography of Madam Walker or A’Lelia Walker.

Stanley Nelson’s 1987 “Two Dollars and a Dream,” was the first documentary about Madam Walker. Nelson, whose grandfather Freeman B. Ransom was general manager and general counsel for the Madam C. J. Walker Manufacturing Company, also directed and produced “BOSS: The Black Experience in Business” a 2019 nonfiction film that includes historically accurate information about Madam Walker.

Here’s the transcript and the video.

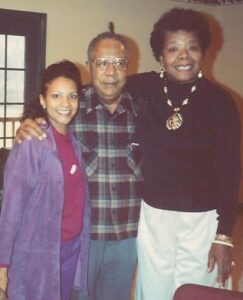

In 1982, Alex Haley, whose fame from the 1976 Roots miniseries still was cresting, approached us about producing a Madam Walker project. For the next several years, Alex was a helpful mentor as I traveled to more than a dozen American cities doing primary source research and interviewing nearly 20 people who had known, worked with or been friends of Madam Walker and A’Lelia Walker.

In 1982, Alex Haley, whose fame from the 1976 Roots miniseries still was cresting, approached us about producing a Madam Walker project. For the next several years, Alex was a helpful mentor as I traveled to more than a dozen American cities doing primary source research and interviewing nearly 20 people who had known, worked with or been friends of Madam Walker and A’Lelia Walker.

On a freighter trip from Long Beach, California to Guyaquil, Ecuador with Alex and two other writers, I finished the manuscript for Madam C. J. Walker: Entrepreneur, a young adult biography published in 1991.

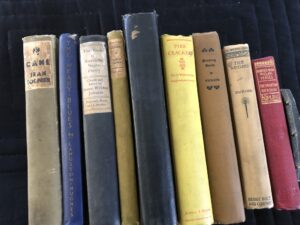

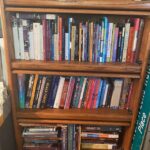

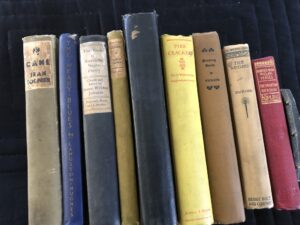

It’s stunning to think this was the first book length biography of Madam Walker ever published, especially now that my personal library is filled with more than 200 books that chronicle Madam Walker’s life from Tiffany Gill’s Beauty Shop Politics, Noliwe Rooks’s Hair Raising and Kathy Peiss’s Hope in a Jar to Hillary and Chelsea Clinton’s The Book of Gutsy Women, Jean Case’s Be Fearless and The Undefeated’s The Fierce 44.

Madam Walker Books in my personal library

And the scholarship continues. Indiana University professor Tyrone McKinley Freeman’s Madam C. J. Walker’s Gospel of Giving: Black Women’s Philanthropy during Jim Crow will be published in November. Since the 1970s, many people have worked together on a range of initiatives to preserve Madam Walker’s legacy. Among the projects:

a campaign for the 1998 Madam Walker U. S. postage stamp

restoration of the Madam Walker Legacy Center in Indianapolis

designation of Villa Lewaro as a National Trust for Historic Preservation National Treasure

digitization of more than 40,000 items in the Madam Walker Collection at the Indiana Historical Society where a 16 month Madam Walker exhibition — You Are There: Madam Walker 1915 –– opened in September 2019

A’Lelia Bundles and Richelieu Dennis, founding CEO of Sundial Brands

renaming of 136th Street at the corner of Malcolm X Boulevard (Lenox Avenue) as Madam C. J. Walker and A’Lelia Walker Place in July 2019

creation of the Madam Walker Family Archives, the largest privately owned collection of Walker records, photographs and memorabilia

dozens of Madam Walker dolls and amazing fine art like Sonya Clark’s large installation at the Austin’s Blanton Museum and Indianapolis’s Alexander Hotel

MCJW, the Madam Walker line of hair care products created by Sundial Brands.

introduction of MCJW, a new line of Madam Walker hair care products manufactured by Sundial Brands and sold exclusively at Sephora.

So, yes, the Netflix series will introduce Madam Walker to many people who otherwise would never have known about her. After you’ve watched the Hollywood version — where the writers have used a great deal of creative license to heighten the drama with characters who didn’t exist and scenes that didn’t occur in real life — we hope you will become curious enough to seek the facts. And of course we hope you will make your way to the new edition of On Her Own Ground as well as some of the blogs about Madam Walker and A’Lelia Walker on this website. There’s also a new audio book that I recorded a few weeks ago.

For updates on all our Madam Walker projects, please visit our Madam Walker Website and follow us on Twitter and Instagram. Click here to sign up for our newsletter.

Professor Tyrone McKinley Freeman, who teaches at Indiana University’s Lilly Family School of Philanthropy, has described the impulse to compare the fortunes of Madam C. J. Walker (1867 – 1919) and Annie Malone (1877* – 1957) as “the first millionaire sweepstakes.” In my observation, this “who was first?” battle has become petty, contrived and counterproductive.

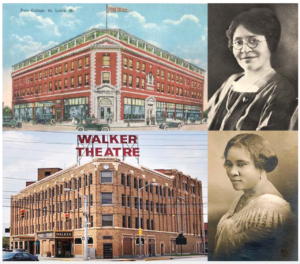

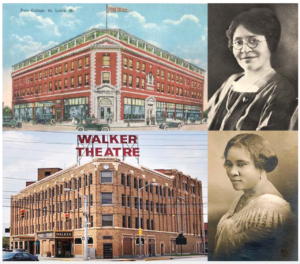

Poro and Walker Building

For a variety of reasons, the now century old rivalry between Madam Walker and Annie Pope-Turnbo Malone continues posthumously with people taking sides in unresolved battles on social media. Most of the time, I try to stay on the sidelines because I long ago learned that it is impossible to change the mind of someone who has no interest in looking at facts and documentation. But for those of you who are open to considering facts, I offer the following information:

There’s no doubt in my mind that Madam C. J. Walker and Annie Malone both are important historical figures who made major contributions as early twentieth century hair care industry pioneers and philanthropists. It is true that Madam Walker sold Malone’s Poro products in St. Louis and in Denver in 1905 and 1906 before marrying Charles Joseph “C.J.” Walker and starting her own Madam C. J. Walker Manufacturing Company. It’s also true that Walker was first introduced to the hair care business in the 1890s by her brothers, who were barbers in St. Louis. As well, it is true that neither Annie Malone or Madam Walker was the first to discover the system of cleansing one’s scalp, then applying a thick ointment that was the consistency of Vaseline — with sulfur as the medicinal agent — to heal the severe scalp infections that were rampant in the early 1900s. It was a time when hygiene was quite different because most Americans lacked in door plumbing. In fact, the remedy they both used had been around for centuries. The basic recipe appears in medical texts as early as the 1700s and was used in other products including Cuticura as well as those manufactured by other black-owned companies during the 1800s. As amazing as both women were, neither was the first to manufacture hair care products for black women. Just a little bit of thought makes it clear that black women had been styling their hair since ancient times.

As a long time journalist and as a biographer who writes non-fiction (i.e. FACT-based) books, I also believe it is important to document one’s assertions and to present accurate information…even on social media where myths and misinformation abound.

Much of the primary source research about the relationship between Walker and Malone first appeared in my book, On Her Own Ground: The Life and Times of Madam C. J. Walker (Scribner, 2001). I was careful to include citations for the newspaper articles and correspondence that documented my assertions in very detailed endnotes. More recently, I wrote a blog post “Madam Walker’s Mentors, Sister Friends and Rivals” that adds to the information about Walker and Malone, as well as the women to whom Walker was close, like St. Louis school teacher Jessie Batts Robinson and anti-lynching activist Ida B. Wells.

Madam C. J. Walker (Credit: Madam Walker Family Archives)

SALES FIGURES FOR MADAM WALKER AND ANNIE MALONE: Since the publication of On Her Own Ground, other authors have written books and articles about Annie Malone. A few years ago, I began to notice “$14 million” as a claim for Malone’s net worth, first in Neema Barnette’s mini-doc video about Malone and then in articles and on social media posts. In 2018, Shomari Wills made the same claim in his book, Black Fortunes: The Story of the First Six African Americans Who Escaped Slavery and Became Millionaires, a poorly researched and error-filled book that had to be revised by his publisher because of the easily found mistakes. For reasons that elude me, he distorted the details of Madam Walker’s life and entirely upended the facts of her appearance and impact at the 1912 National Negro Business League convention.

Because that “$14 million” figure that Wills and others used was new to me, I did additional research to try to learn the origin of the claim. In addition to research I had been gathering for more than 40 years about Walker and Malone, I did an extensive survey of historical newspaper databases on Newspapers.com, Proquest and Genealogybank.com, which now include dozens of black newspapers from the late 1800s and early 1900s.

The first time I was able to find a reference to the $14 million figure was in a 1957 Chicago Defender obituary (“Annie T. Malone Rites at Bethel,” Chicago Defender, May 15, 1957), which read: “Once regarded as the world’s richest Negro woman, her wealth at the peak of her career in the 1920s was estimated at $14 million.”

Two weeks later, the Defender repeated the $14 million figure in another article “How Annie Malone Made, Lost a Fortune.”

In December 1962, the Defender again repeated the $14 million figure.

Annie Malone

But no documentation or business records for this claim were cited in the articles and the figure had never appeared in newspaper reports prior to Malone’s death in 1957. Without such documentation or prior contemporaneous reporting during Malone’s lifetime, the figure seems to be drawn from thin air.

Just as misinformation goes viral today, it seems to have gone viral in 1957 and then to have been resurrected in 2020.

When On Her Own Ground first was published in 2001, I estimated Madam Walker’s personal wealth (homes, real estate investments, jewelry, cars, clothing, furniture, etc) to be between $600,000 and $700,000. However, a business historian pointed out to me a year later that I had failed to include the value of Madam Walker’s company in my estimation of her wealth. When one takes into account the sales for the last two years of her life and the year following her death, I was advised that the value of her company, had it been sold on the day of her death, would have been between $1 million and $2 million in 1919 dollars.

Here are the gross receipts for 1918 – 1920 (as documented in Walker Company annual reports and tax records in our Madam Walker Family Archives and in the Walker Collection at the Indiana Historical Society):

1918 earnings: $275,937.88 (an increase of $100,000 from 1917)

1919 earnings $486,762

1920 earnings: $595,353 (or $9,272,135.87 in 2020 according to Dollar Times Calculator)

We are fortunate that we can document Madam Walker’s sales because of the voluminous records that were preserved from the Madam C. J. Walker Manufacturing Company. Unfortunately, similar documentation does not exist for the Poro Company. Unless such records surface, there is no way to prove the claims about Malone’s wealth.

During the last four decades, I’ve created a file of hundreds of articles that mention Malone or Poro between 1903 and the time of her death in 1957. Some of those articles quote officials of the Poro Company regarding the claims for annual sales and company value. I have not found any articles prior to Madam Walker’s death in 1919 or Annie Malone’s death in 1957 that claimed that Malone was “worth $14 million.”

Instead I have found the following:

In November 1913 the Cleveland Gazette, where Annie (then Pope-Turnbo) frequently advertised, the Doings of the Race columnist wrote, “An expert going over the books found the receipts from the sale of hair preparations and agents fees total from $100 to $150 per day.” The Chicago Defender also carried a story giving the $100 to $150 per day” figure.

That $100 to $150 per day would be between $36,500 and $54,750 annually if received seven days a week or between $26,100 and $39,150 annually based on Monday through Friday receipts.

In August 1915, in response to a law suit brought by Walter Majors (a former Malone business partner who sued her for reneging on a share of the 1913 profits she had promised him), a report of the earnings of the previous 33 months was $63,650.03 gross with $24,333.60 net. Another article says the period was “fourteen months” with a “monthly net profit of $1,738.” (14 x $1,738 = $24,333.60).

1918: “A $50,000 Corporation with $250,000 Yearly Business…From last year’s statistics, presented [to] the Bee reporter, is shown in round numbers $250,000 business done.” (“Notable Career of Prof. and Mrs. A.E. Malone,” Washington Bee, August 31, 1918) [Walker’s gross receipts that year, as documented in the annual report prepared by her attorney, were $275,937.88.]

1924: In November, the Topeka Plaindealer reported that Malone had “paid $38,408 income tax for 1923. Her business represents an investment of $750,000.” (“She Is Solving the Race Question,” Plaindealer (Topeka, KS), November 14, 1924)

1926 “Mrs. Malone is probably the Race’s leading business woman and is known to be worth several millions of dollars.” [though I will point out that this reporter cites no documentation] (“Former Banker’s Home Brings Nearly $50,000,” Philadelphia Tribune, Jan 30, 1926)

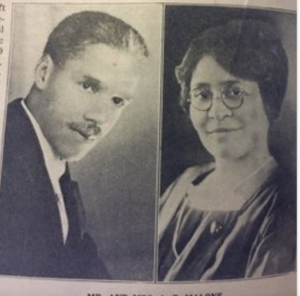

Aaron Malone and Annie Pope Turnbo married in 1914

WHY IS MADAM WALKER MORE WELL-KNOWN THAN ANNIE MALONE: There are many possible reasons why Madam Walker is more well-known today than Annie Malone. Madam Walker died at the height of her fame in May 1919 with her wealth intact while Malone experienced business and reputational setbacks during the 1920s after a contentious divorce from Aaron Malone, who worked to turn some of her employees against her and to undermine her leadership role.

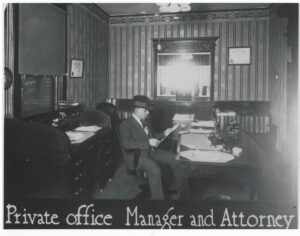

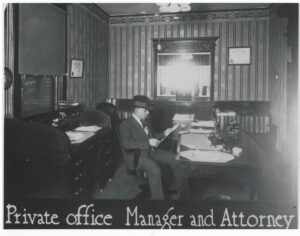

Madam Walker had a knack for hiring and empowering strong leaders who enhanced her company. Her carefully selected executive team included Freeman B. Ransom, the attorney who guarded against legal threats, while Malone was involved in a decades long lawsuit brought by Walter Majors, a former business partner, who accused her of failing to pay a portion of profits promised to him in 1913. (Among the articles that document this legal battle is “Referee Finds Against Beauty Specialist,” Indianapolis Freeman, August 28, 1915.)

Madam C. J. Walker Mfg. Co. Atty F. B. Ransom circa 1912 (Madam Walker Family Archives)

While Attorney Ransom steadfastly paid Madam Walker’s personal and corporate federal income taxes, Malone disputed her federal tax assessment and faced a large unpaid federal tax bill during the 1940s.

Madam Walker’s secretary Violet Davis Reynolds, who worked for the Walker Company from 1914 until 1979, kept meticulous records and preserved thousands of Walker’s personal letters and financial documents, which are housed at the Indiana Historical Society. There is no comparable body of records for Annie Malone or the Poro Company.

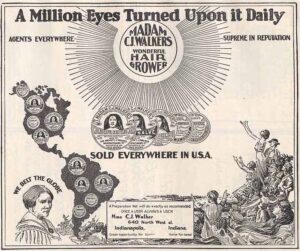

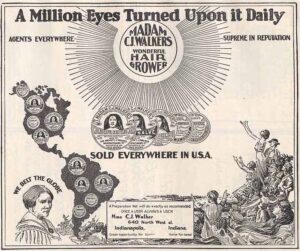

Madam Walker advertised heavily in the black press and cultivated relationships with black editors and publishers. Like her contemporaries Helena Rubinstein and Elizabeth Arden, she created national distribution platforms for her products. She traveled to the Caribbean and Central America in 1913 to expand her market internationally.

Madam Walker advertised in dozens of black newspapers.

Another factor may be her daughter A’Lelia Walker’s suggestion that they establish a presence in Harlem in 1913 just as this uptown Manhattan neighborhood was becoming a political and cultural mecca for African Americans. A’Lelia Walker operated the Walker Beauty School and Salon in Harlem, then converted a floor of their 136th Street townhouse into The Dark Tower, which became an iconic gathering place for the artists, writers, musicians, actors and celebrities of the Harlem Renaissance.

By the mid-1970s most of the Poro and Walker Beauty Schools had closed. I have not been able to determine when the Poro Company stopped manufacturing its line of hair care products. The Madam C. J. Walker Manufacturing Company never went out of business. The trademark was sold by the Madam Walker trustees in the early 1980s to an entity that manufactured some of the original formulas for the next three decades.

MADAM by Madam C. J. Walker at Walmart

In 2013 Richelieu Dennis, founder of Sundial Brands, acquired the Walker trademark for cosmetics and hair care products and revived the line with all new formulas. Today the MCJW line is sold exclusively at Walmart stores and at Walmart.com.

Madam Walker’s legacy also benefits from two very tangible reminders. The Madam Walker Legacy Center in Indianapolis is a National Historic Landmark. Villa Lewaro, the mansion designed by architect Vertner Tandy (a founder of Alpha Phi Alpha), is both a National Historic Landmark and one of the National Trust for Historic Preservation’s designated National Treasures.

Villa Lewaro, estate of Madam C. J. Walker, 1924 (Madam Walker Family Archives0

So who was first? Madam Walker or Annie Malone? If you’ve made it this far in the article, you know that Madam Walker’s wealth can be documented while Annie Malone’s can not. My personal perspective is that Madam Walker’s legacy is measured more in the jobs she created, the philanthropy she dispensed, the lives she changed and the seeds she planted for political activism than in whether she was “the first self-made American woman millionaire,” as the Guinness Book of World Records states.

So those who want to keep arguing this point can have at it.

If you’re interested in learning more about Madam Walker and what’s truly important about her legacy, we urge you to read the new edition of On Her Own Ground: The Life and Times of Madam C. J. Walker or listen to the audio book that I recently recorded. If you happen to be in Indianapolis, we hope you’ll visit the Madam Walker Legacy Center and the Indiana Historical Society where a major exhibit — “You Are There: Madam Walker 1915 Empowering Women” — is up until January 2021.

*Malone was born in 1877. This is a correction.

I’ve written a lot about Madam C. J. Walker’s professional and financial achievements, but to truly understand who she was at her core, I’ve also examined her relationships with other women: her mentors, her sister friends and her rivals.

Madam C. J. Walker circa 1913 (Madam Walker Family Archives/aleliabundles.com)

Madam Walker is perhaps best known as a millionaire entrepreneur and hair care industry pioneer, who defied the odds. Behind that public persona is a more private person who valued and benefited from her friendships with other women.

This is not to ignore the men in her life. Her three brief marriages – one husband died and the other two cheated on her – surely motivated her to be self-sufficient. She made much wiser choices in selecting her male business associates, especially Freeman B. Ransom, the attorney who became the Walker Company’s longtime general manager. And she valued business and political collaborations with men like Indianapolis Freeman publisher George Knox, Crisis editor W. E. B. Du Bois, Tuskegee Institute principal Booker T. Washington, musician James Reese Europe and Messenger publisher A. Philip Randolph.

Madam C. J. Walker Mfg. Co. Atty F. B. Ransom circa 1912 (Madam Walker Family Archives)

And of course her relationship with her daughter, A’Lelia Walker, is central to understanding what made her tick. (I’ve written about this in On Her Own Ground: The Life and Times of Madam C. J. Walker and will have much more to say in my in-progress book, The Joy Goddess of Harlem: A’Lelia Walker and the Harlem Renaissance.)

A’Lelia Walker, daughter of Madam C. J. Walker (Madam Walker Family Archives)

But it is Madam Walker’s early experiences of being helped by other women that made her so devoted to empowering her sales agents and to supporting causes and organizations that helped girls and women. “I am not merely satisfied in making money for myself, for I am endeavoring to provide employment for hundreds of women of my race,” she said at the 1914 National Negro Business League Convention.

In 1917, at the first national convention of the Madam C. J. Walker Beauty Culturists Union, she implored the delegates to use part of their earnings to better their communities. “I want my agents to feel that their first duty is to humanity,” she said. “Let the world know that the Walker agents are ready to do their bit to help and advance the best interests of the Race.”

When Sarah Breedlove McWilliams moved from Vicksburg, Mississippi to join her older brothers in St. Louis in 1888, she was a 20-year old widow with a two-year old daughter. It was the women of St. Paul African Methodist Episcopal Church and the Mite Missionary Society who helped her see that she could aspire to something more than a life of drudgery as a washerwoman.

Jessie Batts Robinson, St. Louis teacher and clubwoman, who mentored Madam Walker (Madam Walker Family Archives)

Jessie Batts Robinson, a schoolteacher and St. Paul’s member, took a particular interest in Sarah and her daughter. The home Jessie shared with her husband (and St. Louis Argus editor), Christopher “C. K.” Robinson, was a refuge for the struggling young mother. As national officers of the Knights of Pythias and the Court of Calanthe, they exposed Sarah to the powerful network of black fraternal organizations.

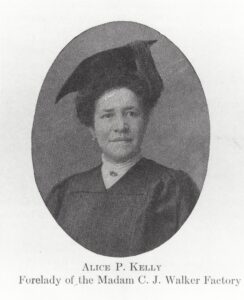

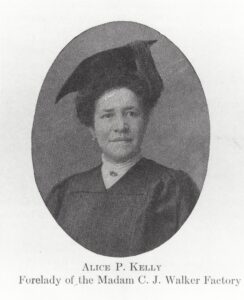

After she founded the Madam C. J. Walker Manufacturing Company in 1906, Madam Walker intentionally surrounded herself with skilled and educated employees. She had a talent for identifying leaders and encouraging them to shine. Aware that her own lack of formal education could be a hindrance, she sought employees who could help shore up her deficits. She considered it a coup that Alice Kelly, dean of girls at Kentucky’s Eckstein Norton Institute, agreed to join the Walker Company as “forelady” – or manager – of her factory.

Kelly also served as her private tutor and sometimes traveling companion. Violet Davis Reynolds, who began working at the Walker Company as a secretary in 1914, later described the role Kelly played in helping Walker polish her presentations: “Whenever I traveled with them, I remember Madam asking Miss Kelly immediately after her speech, ‘How did I do? How can I do better?’”

Alice Kelly, Manager of the Madam Walker Factory (Madam Walker Family Archives)

That desire to improve – from her handwriting to her grammar – was critical to her success.

As with any successful entrepreneur, Madam Walker also had competitors, most notably Annie Turnbo Pope Malone. It is true that Sarah Breedlove McWilliams sold Malone’s Poro products for about a year in St. Louis and then in Denver. Not long after she married Charles Joseph “C. J.” Walker in early 1906, there was a rift of some kind between the two women that caused Madam Walker to sever ties with Malone. By April of 1906 Madam Walker was selling her own line of hair care products.

I’ve written about this fissure in On Her Own Ground and have expanded upon the rivalry in a recent blog article (“The Facts about Madam Walker and Annie Malone”) where I address the difficulty in documenting whether Malone was a millionaire, too. We are fortunate that F. B. Ransom and Violet Reynolds were such conscientious record keepers. As a result, thousands of pages of Madam Walker’s personal and business correspondence are preserved at the Indiana Historical Society. There is no comparable set of records for Annie Malone or the Poro Company.

After decades of research, I’ve come to believe that the relationship with Malone was an important catalyst that helped Sarah Breedlove McWilliams escape St. Louis and a troubled second marriage. But I’ve also come to think the relationship was more transactional than collaborative.

Both women were successful entrepreneurs and philanthropists whose legacies are important in the history of American business. But these two women made very different decisions about how they ran their businesses, the people they chose to put in leadership positions and their marketing strategies.

The women whom Madam Walker would have named as her mentors are Jessie Batts Robinson and Alice Kelly. Among those she truly admired and counted as friends were women like anti-lynching activist Ida B. Wells, Mary Burnett Talbert (the NAACP organizer and former National Association of Colored Women president who led the drive to preserve Frederick Douglass’s home) and educator Mary McLeod Bethune.

Ultimately Madam Walker’s story is one of women empowering and supporting each other, then using their leadership and financial profits to better their communities and the lives of their families.

If you’d like to learn more about Madam Walker, we hope you’ll read On Her Own Ground: The Life and Times of Madam C. J. Walker by A’Lelia Bundles.

Other blog articles

The Centennial of Madam Walker’s Death

A’Lelia Walker was born 134 years ago today on June 6, 1885.

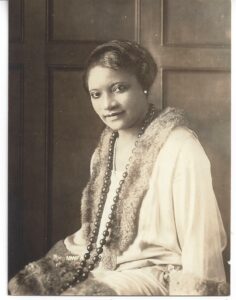

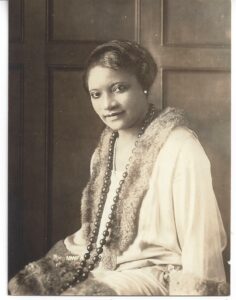

I’ve written a lot about her since I began researching her life during my senior year in high school fifty years ago. I won’t rehash the basic biographical information, which you can find in my book, On Her Own Ground: The Life and Times of Madam C. J. Walker, and in blog articles like “A’Lelia Walker’s 1924 Visit to Atlantic City” and “A’Lelia Walker Meets Ethiopian Empress Zauditu” on my website.

I’ve written a lot about her since I began researching her life during my senior year in high school fifty years ago. I won’t rehash the basic biographical information, which you can find in my book, On Her Own Ground: The Life and Times of Madam C. J. Walker, and in blog articles like “A’Lelia Walker’s 1924 Visit to Atlantic City” and “A’Lelia Walker Meets Ethiopian Empress Zauditu” on my website.

What I’d like to do today in celebration of her birthday is talk about the person I’ve discovered through extensive research – including her personal correspondence and other primary source documents – rather than the caricature that a number of authors have created.

First and foremost, she will always be known as the daughter of Madam C. J. Walker, the early 20th century hair care entrepreneur and philanthropist. But she also was her own person with interests, personality traits, likes, dislikes and a fascinating circle of friends.

More than I knew when I wrote On Her Own Ground twenty years ago, she was very much a patron of the arts with her own strong passion for music and art that began when she was growing up in St. Louis during the ragtime era of the 1890s. She traveled internationally and understood current events and the politics of Jim Crow. She had an impresario’s instinct for staging extravagant events.

She was a fashion trendsetter with a sharp eye for design. Her parties helped define the Harlem Renaissance. Her Dark Tower cultural salon was legendary. While she was less directly engaged than her mother in causes like the anti-lynching and women’s club movements, she raised money for community and social service organizations.

How Other Authors Viewed A’Lelia Walker

My literary introduction to A’Lelia Walker was through Langston Hughes’s The Big Sea, in which he famously proclaimed her death in August 1931 to be the end of an era. “That was really the end of the gay times of the New Negro era in Harlem,” he wrote. It is Hughes who anointed her “the joy goddess of Harlem’s 1920s” because of her parties and her room-filling personality.

What I have discovered after decades of research, however, is that several other authors who did not know her have repeated second hand, inaccurate and entirely fabricated stories about her. It’s hard to resist wondering if some of them have a need to project a story line onto her life. In their speculation and their failure to do original research, they have relied upon stereotypes and clichés about what they imagine A’Lelia Walker might have done.

What I have discovered after decades of research, however, is that several other authors who did not know her have repeated second hand, inaccurate and entirely fabricated stories about her. It’s hard to resist wondering if some of them have a need to project a story line onto her life. In their speculation and their failure to do original research, they have relied upon stereotypes and clichés about what they imagine A’Lelia Walker might have done.

I very much admire David Levering Lewis’s Pulitzer Prize-winning scholarship on W.E.B. DuBois, but his description of A’Lelia Walker in his widely read When Harlem Was in Vogue set the stage for a great deal of misinformation about her. Just as I discovered while doing research for my four Madam Walker books, I have encountered the same fictionalization of A’Lelia Walker while researching The Joy Goddess of Harlem: A’Lelia Walker and the Harlem Renaissance (forthcoming from Scribner). In all her complexity and contradictions, A’Lelia Walker is an original who needs no embellishment.

I won’t address all the myths today, but here are three of the most glaring.

The Myth of A’Lelia Walker’s Short Attention Span

In 1982 Lewis wrote: “Her intellectual powers were slight. After seven minutes, conversation went precipitously downhill, but those first seven minutes were usually quite creditable.” Among the many authors who have mentioned A’Lelia Walker since then, Steven Watson perpetuated this myth in his 1995 book, The Harlem Renaissance, when he wrote: “One acquaintance cattily declared seven minutes to be her limit for elevated conversation.”

I’ve always found this claim odd. During the early 1980s, I had the good fortune of interviewing a dozen or so of A’Lelia Walker’s octogenarian and nonagenarian friends who regaled me with stories of their social gatherings and travels. To a person, they described A’Lelia’s attention to detail for the elegant parties she orchestrated. I know from her letters how focused she could be when she cared about something. I can’t help but wonder if, by chance, someone actually said she had a seven-minute attention span, that that person may have been someone she didn’t like or with whom she didn’t wish to have a conversation. She could be like that when she wanted to.

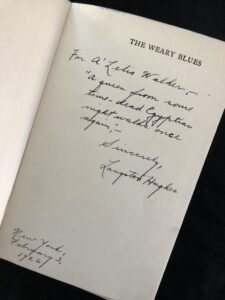

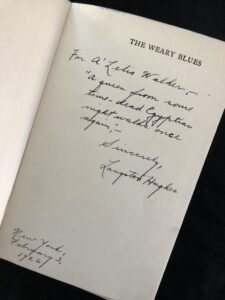

The Myth that A’Lelia Walker Didn’t Read Books

Watson seems to have started this rumor when he wrote: “Although she supported Harlem culture, she had little interest in intellectual talk and rarely read books.” More recently Saidiya Hartman paraphrased Watson and others in her 2019 book when she wrote: “[S]he financed the Dark Tower, a literary salon in her palatial home of thirty rooms, although it was rumored that she never read books, only supported their authors.” (The Dark Tower, by the way, was in A’Lelia Walker’s 136th Street townhouse rather than in Villa Lewaro, her Irvington, New York mansion.) Neither Watson or Hartman cites a source for this claim.

In fact, I have many books from A’Lelia Walker’s personal library, including an autographed copy of Langston Hughes’s The Weary Blues. I also have personal correspondence in which she thanks friends for books they have sent her and talks about how much she loves to read.

In fact, I have many books from A’Lelia Walker’s personal library, including an autographed copy of Langston Hughes’s The Weary Blues. I also have personal correspondence in which she thanks friends for books they have sent her and talks about how much she loves to read.

The Myth that Grace Nail Johnson Wouldn’t Socialize with A’Lelia Walker

One of the most memorable passages in Lewis’s When Harlem Was in Vogue is this: “Not everybody pined for an invitation to her brownstones and her country place. Grace Nail Johnson, the wife of James Weldon Johnson and ‘social dictator’ of Harlem, would as soon have done the Black Bottom on Lenox Avenue as cross A’Lelia’s threshold.”

These sentences have taken on a life of their own in Harlem Renaissance lore and been accepted as factual by readers and authors who have interpreted it to mean that A’Lelia Walker was shunned by Grace Nail Johnson and Harlem’s black elite.

In August 1999 Sondra Kathryn Wilson, the executor of the Johnson estate, told me in an email message that Mrs. Johnson was quite upset about this portrayal.

“It’s a lie,” she told Dr. Grace Sims Okala, her adopted daughter, in an interview recorded some years earlier by Wilson. “Grace and Jim considered the older Mrs. Walker as their friend. Grace often said that the elder Mrs. Walker and her father had similar backgrounds…Grace and Jim didn’t attend a lot of parties. Jim traveled a lot. He was gone so much and when he was home, he was writing. Grace and Jim preferred small dinner parties. If Grace didn’t attend the younger Ms. Walker’s parties, it had nothing to do with Ms. Walker. I know she wouldn’t attend a party if Jim was away. She wouldn’t have gone to Mrs. Walker’s or any other party alone.”

And I know from A’Lelia Walker’s correspondence – including an invitation for an event that lists both A’Lelia Walker and Grace Nail Johnson as hosts – that the speculation about their estrangement is inaccurate. Among other things, the spirit and implication of the story are contradicted by what society columnist Gerri Major, singer Alberta Hunter, artist Romare Bearden and many others told me about A’Lelia Walker during the 1980s.

There is so much more to say about my great-great-grandmother and namesake. Stay tuned for The Joy Goddess of Harlem.

On Sunday morning, May 25, 1919 – exactly 100 years ago this weekend – Madam C. J. Walker died at Villa Lewaro, her Irvington-on-Hudson, New York estate.

A few hours later in black churches across America, ministers talked of her journey from deep poverty in the cotton fields of Delta, Louisiana to president of the international Madam C. J. Walker Manufacturing Company. It was such big news that the announcement also was made at a Negro League baseball game in Chicago that afternoon.

Madam C. J. Walker died on May 25, 1919 at Villa Lewaro, her Irvington, NY estate.

She was born Sarah Breedlove on December 23, 1867 on the same plantation where her parents and older siblings had been enslaved before the end of the Civil War. The first child in her family born into freedom, she would become a millionaire who bequeathed more than $100,000 to her community, including $5,000 to the NAACP’s anti-lynching fund.

By providing job opportunities for the nearly 20,000 sales agents and beauty culturists who sold her Wonderful Hair Grower, she helped them become economically independent. She used her wealth and influence as a philanthropist, patron of the arts and political activist to support black institutions and organizations.

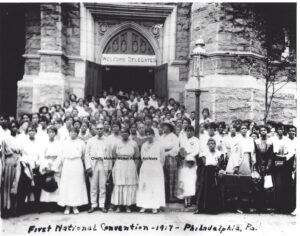

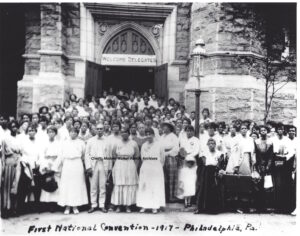

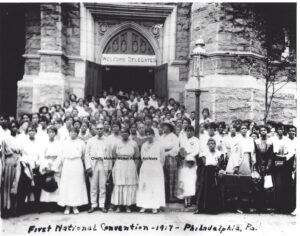

Madam Walker at her first national convention of her sales agents and beauty culturists in 1917.

At her 1917 national convention, she told the delegates that their “first duty” as Walker associates “was to humanity.” During the final session, she and her agents dispatched a telegram to President Woodrow Wilson urging him to support legislation to make lynching a federal crime.

Madam Walker’s funeral on May 30 was a dignified gathering with pallbearers who represented black America’s most prominent civil rights, business and religious leaders. Walker Company employees and agents filed quietly and reverently past her casket in the music room at Villa Lewaro as J. Rosamond Johnson sang “Since You Went Away,” the spiritual he had composed with his brother, James Weldon Johnson.

This year as we observe the centennial of Madam Walker’s death, there is much to remind us of the powerful inspiration her legacy still provides.

Throughout 2019 and 2020 we’ll celebrate with several events including

*the launch of new products in Sundial’s MCJW hair care line at Sephora.com

MCJW, the Madam Walker line of hair care products created by Sundial Brands.

*the re-opening of the renovated Madam Walker Legacy Center in Indianapolis

*the September 19 opening of a Madam Walker exhibition at the Indiana Historical Society in Indianapolis

*the renaming this summer of 136th Street between Lenox and Seventh Avenue in Harlem

*the digitization of 40,000 items from the Madam Walker Collection of letters, photographs, business records and ephemera at the Indiana Historical Society

This spring we’ve already had help celebrating with

*a featured segment about Madam Walker in Stanley Nelson’s PBS documentary, “BOSS: The Black Experience in Business”

*Harlem Eat Up Luminary Award to Madam Walker

*”What Madam Taught Us” in the May issue of Essence

*AAIHS’s five-part Black Perspectives blog forum with articles by scholars who bring new perspectives on Madam Walker’s life

*Our interview with Georgia Public Broadcasting’s Morning Edition host Leah Fleming

ABC News Now’s segment about Villa Lewaro

Ronda Racha Penrice’s NBC BLK feature on Madam Walker

During the last four decades in my role as Madam Walker’s biographer, it has been a joy for me to share her story with a range of audiences from elementary school students and Harvard Business School classes to corporate CEOs and women in the college course at Bedford Hills Correctional Facility.

Madam Walker biographies by A’Lelia Bundles

I’m grateful that my book, On Her Own Ground: The Life and Times of Madam C. J. Walker (Scribner/Lisa Drew 2001), is considered the most reliable source for accurate information about Madam Walker and that elementary school students can learn about her in All About Madam C. J. Walker (Cardinal/Blue River Press 2018).

Knowing that Villa Lewaro soon will become a think tank for women of color entrepreneurs under the auspices of the New Voices Foundation brings the story full circle just as Madam Walker dreamed when she moved into the house in 1918.

Follow us on Twitter at @aleliabundles @mcjwbeauty @madamcjwalker

Follow us on Instagram at @aleliabundles @mcjwbeauty

A’Lelia Bundles is Madam C. J. Walker’s great-great-granddaughter and biographer.

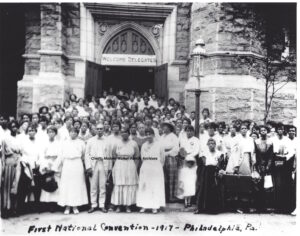

One hundred years ago this week — on August 30 and August 31, 1917 — hair care entrepreneur Madam C. J. Walker hosted the first annual convention of her sales agents and beauty culturists. More than 200 women gathered at Philadelphia’s Union Baptist Church to hear Walker’s message about entrepreneurship, civic responsibility and political activism.

At one of the first conventions of American businesswomen, the delegates shared stories of how their work as Walker agents had transformed and enriched their lives.

With few career opportunities open to black women during the early twentieth century, many had been maids, washerwomen, cooks and sharecroppers. A few had been teachers and nurses. Now they talked of the financial rewards that allowed them to purchase homes, educate their children and contribute to their churches and community organizations.

1917 Convention of Madam Walker agents in Philadelphia (Madam Walker Family Archives)

Margaret Thompson, president of the Philadelphia Union of Walker Hair Culturists told her colleagues that she had earned $5 a week as a servant. Now she claimed an income of $250 a week (the equivalent of more than $5,200 in 2017 dollars).

On the final day of the convention Madam Walker’s theme was “Women’s Duty to Women.” She envisioned these economically successful women as community leaders and agents of change. To emphasize the point, she gave $500 in prizes, not only to the women who had sold the most tins of Madam Walker’s Wonderful Hair Grower, but to those whose local Walker clubs had contributed the most to charity.

At the end of the convention, the women sent a telegram to President Woodrow Wilson urging him to support legislation that would make lynching a federal crime.

“We, the representatives of the National Convention of the Madam C. J. Walker Agents, in convention assembled, and in a larger sense representing twelve million Negroes, have keenly felt the injustice done our race and country through the recent lynching at Memphis, Tennessee, and the horrible race riot at East St. Louis.”

“Knowing that no people in all the world are more loyal and patriotic than the Colored people of America, we respectfully submit to you this our protest against the continuation of such wrongs and injustices in this ‘land of the free and the home of the brave’ and we further respectfully urge that you as President of these United States use your great influence that Congress enact the necessary laws to prevent a recurrence of such disgraceful affairs.”

The Madam C. J. Walker Manufacturing Company continued a tradition of annual conventions through the early 1960s.

Today the Madam C. J. Walker Beauty Culture line of hair care products is manufactured by Sundial Brands and sold nationwide at Sephora.Madam C. J. Walker Beauty Culture (mcjwbeautyculture.com)

When I was a toddler eating dinner with my parents, there was no way for me to know that our silverware — with its “CJW” monogram — would inspire four books, including On Her Own Ground: The Life and Times of Madam C. J. Walker, the biography that provided the factual material for the fictionalized four-part Netflix series.

When I was a toddler eating dinner with my parents, there was no way for me to know that our silverware — with its “CJW” monogram — would inspire four books, including On Her Own Ground: The Life and Times of Madam C. J. Walker, the biography that provided the factual material for the fictionalized four-part Netflix series.

In 1982, Alex Haley, whose fame from the 1976 Roots miniseries still was cresting, approached us about producing a Madam Walker project. For the next several years, Alex was a helpful mentor as I traveled to more than a dozen American cities doing primary source research and interviewing nearly 20 people who had known, worked with or been friends of Madam Walker and A’Lelia Walker.

In 1982, Alex Haley, whose fame from the 1976 Roots miniseries still was cresting, approached us about producing a Madam Walker project. For the next several years, Alex was a helpful mentor as I traveled to more than a dozen American cities doing primary source research and interviewing nearly 20 people who had known, worked with or been friends of Madam Walker and A’Lelia Walker.

I’ve written a lot about her since I began researching her life during my senior year in high school fifty years ago. I won’t rehash the basic biographical information, which you can find in my book,

I’ve written a lot about her since I began researching her life during my senior year in high school fifty years ago. I won’t rehash the basic biographical information, which you can find in my book,

What I have discovered after decades of research, however, is that several other authors who did not know her have repeated second hand, inaccurate and entirely fabricated stories about her. It’s hard to resist wondering if some of them have a need to project a story line onto her life. In their speculation and their failure to do original research, they have relied upon stereotypes and clichés about what they imagine A’Lelia Walker might have done.

What I have discovered after decades of research, however, is that several other authors who did not know her have repeated second hand, inaccurate and entirely fabricated stories about her. It’s hard to resist wondering if some of them have a need to project a story line onto her life. In their speculation and their failure to do original research, they have relied upon stereotypes and clichés about what they imagine A’Lelia Walker might have done.

In fact, I have many books from A’Lelia Walker’s personal library, including an autographed copy of Langston Hughes’s The Weary Blues. I also have personal correspondence in which she thanks friends for books they have sent her and talks about how much she loves to read.

In fact, I have many books from A’Lelia Walker’s personal library, including an autographed copy of Langston Hughes’s The Weary Blues. I also have personal correspondence in which she thanks friends for books they have sent her and talks about how much she loves to read.

Recent Comments